Science Fiction, Hard and Otherwise

This blog is not entirely about space, but space travel is, shall we say, a prominent topic of discussion. I recently got an email from a reader who made what might be a controversial observation: "I like my starships with a little bit of swoosh."

So, how much swoosh is a starship allowed to make, and who decides? One of the first good things I heard about Firefly, before I'd seen any episodes, was that it had a silent rifle shot in space. This alone was reason enough to check out into the next episode. As it turned out, if I was looking for Realism [TM] I'd have been better off sticking with the World Series, which was then chasing Firefly around the TV schedule. So far as scientific and technical realism goes it was modest even by Hollywood standards, which is to say not at all.

All the same Firefly hooked me, the first TV scifi show to do so since Babylon 5. It did have another sort of realism that I like, and which is also rare in Hollywood scifi – a milieu set in an era clearly not our own, with differences of clothing, customs, even language. By comparison, I was never tempted to try Battlestar Galactica because even its admirers agreed that its space military was portrayed as an operational and cultural dead ringer for the present day USN.

But mostly Firefly pulled me in because while at bottom it was a shameless Bat Durston, it was a really good Bat Durston. Story trumps realism, and character trumps everything.

Rocketpunk Manifesto deals largely with hard SF and Realistic [TM] future space tech mainly because these things are an interesting mental game in their own right. Spacecraft behave in ways almost entirely unlike terrestrial vehicles. If you want to have, say, a space battle – and judging from my traffic, a good many of you do – it is interesting to explore how it might play out within the constraints of known physical laws and foreseeable technology for exploiting them.

Also, of course, barring a Huge Scientific Revolution, this is the way actual future spacecraft will behave. Science fiction, especially hard SF, has a close if somewhat uneasy relationship to futurology and what might really happen. So much so that retro-futurism – portrayals of the future as it used to be – has become an established SF subgenre. Thus steampunk, inspired by the early SF of a century ago, and at least potentially rocketpunk, inspired by that of 50 years ago.

Hard SF also has a somewhat uneasy relationship with the rest of science fiction, not to mention the rest of literature. In emphasizing technical realism it occupies roughly the same place in SF that police procedurals do in the mystery genre. But there's also a case, as Eric Raymond argues, that hard SF is in some sense the core of SF – as SFnal as it gets. Which also puts it at the heart of the SF literary ghetto. To the general public, 'scifi' still means, especially, spaceships – even though Hollywood has made two successful and highly regarded historical period pieces about space travel.

There is a whole wing of SF criticism that is not especially happy about this, and subgenres such as slipstream make a fairly deliberate effort to emphasize the weird, and blur the lines between SF and the rest of Romance, and for that matter between Romance itself and 'mainstream' – a branch of literature that oddly enough is far more essentially concerned with realism than hard SF is. But I think Raymond is right in some important way; hard SF typifies what distinguishes SF from its genre cousins.

That said, the, um, hard truth is that even most of hard SF is, in its heart of hearts, space opera. My posts on space warfare are the most popular I've done on this blog, and probably are what brought a good many of you here. From a Realistic [TM] perspective, space armadas or 'constellations' are none too likely – it is indicative that even though the Space Age began amid superpower rivalry and continued that way for a generation, neither side ever found reason to build and deploy space warcraft. But it makes for cool space opera.

And the dialogue between hard SF and the rest of SF – and the rest of Romance – can be a productive one. Any FTL setting is, almost definitionally, not really hard SF, since the whole setting relies on women chanting in Welsh. But plausible-sounding tech can play the same role in faking realism that convincing-looking swordplay does in a swashbuckler or fantasy story. For fans of non-hard SF – even space fighters – I hope that this blog will at least give you twists and variations to think about. But if you're reading this, you probably already guessed that.

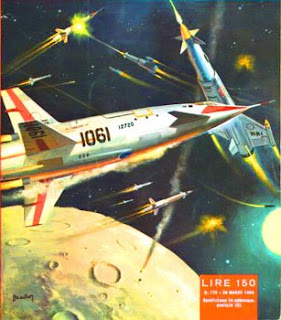

Related links: The dialogue in action: my post on space fighters is still getting comments after nearly two years. And the temple of hard SF information, Atomic Rockets, is as richly ornamented with non-hard artwork (including the image above) as a Gothic cathedral. I discussed rocketpunk as such early on (surprise!), and later mulled the possibility of hard SF.

31 comments:

Ah, the old argument of Realistically Hard Sci-Fi vs Hollywood Logic. We've all heard the arguments that the science shown in Hollywood movies, television shows, and the like are as accurate as the existence of WMDs in Iraq back in '03 (too soon?).

I admit, that the only Sci-Fi stories that are even remotely considered "Hard" are the "Cold Equations" short story and the "Starship Troopers" novel. And yes, I have been spoiled by what was produced in not just Hollywood movies and TV, but also space battles in the realm of video games. However, playing Devil's Advocate, most movie going audiences (that legitimately and legally paid to watch) aren't exactly watching the various media mediums to learn. If that were the case, well let's just say that we'd be seeing far less internet videos featuring people doing obviously stupid stunts.

Though Hard Sci-Fi novels are fun to read if only to provoke the thought experiments of how the future might work and such, Hard Sci-Fi media outside the written word is extremely hard to make exiting, let alone profitable. This video, especially at the time mark of 7:08 - 7:45, illustrates my point exactly:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8Spz-wOiwpo

Though I find your notation on Hard Sci-Fi being a Space Opera at its very heart and core rather interesting and thought provoking. Even though science as we know it would not allow the kind of future, and by extension interplanetary and interstellar combat, that is often portrayed in Sci-Fi of all mediums regardless of their accuracy or not, it still doesn't halt the numerous sci-fi stories from being written and published. Nor does it stop an individual from reading the story and getting the feeling of being immersed in that world with its sense of plausibility and familiar yet with hints and clues of the exotic and alien.

However, personally I am a bit miffed- no *bleep*ing ticked off that all the Sci-Fi novels have been relocated to the "Fantasy" Section as of late.

On another note, I am glad that the post I have done on June 13th of this year was read and later replied. When I had made that post, it was about the same time Atomic Rocket was doing its Twitter Updates and I absentmindedly made the post without looking at the year in which it was made. I honestly didn't think that it would have been replied even days after the post was made to see if there was the reply. It was originally longer and more detailed, but there was a limit to how much I could type and post so I had to condense it and make sure that my point was made clear.

- Sabersonic

Personally I'd say Hard SF occupies the same space in SF that Technothrillers occupy in modern thriller novels. The police procedural comparison doesn't quite work because cop novels, due to the nature of cop work, are all about people colliding in spectacular ways. Technothrillers and Hard SF are about the gear and (Sometimes) how people deal with the gear.

But that's a minor quibble. The truth is most Hard SF (And most technothrillers) are dated within a few years of publication. Anyone else remember those brain-controlled super-sophisticated fighter jets the Mighty Soviet Empire built back in the Eighties?

Ian_M

If you would indulge in some very general speculation: the following are mere idle and very general musings, certainly not meant to apply to specific cases, so I will not name names nor use examples... hardly a scientific process, so you already can see the author bias in this post. A very quick background: I was enrolled in an aeronautical engineering college for several years until I abandoned those studies and enrolled into an arts college. I did not drop out because of failure, but personal discovery. Take what limited insight this gave me with a huge grain of salt.

I tend to think that the main reason Hard SF seems to be rather less than popular is not an intrinsic problem with the medium, nor with the relative hardness of its presentation, but due to a rather important, and fundamental, flaw: the author. He comes in two flavors:

In the case of "scientist first, writer second", we get someone whose main interest is in the accurate mathematical and physical facts, rules and laws that govern the Universe. When turned into an author, his obvious bias will be toward his chosen subject, and he will no doubt be fascinating for him and people in his field. No one else will understand a word in ten. He might or might not have taken writing classes or belonged to a writer's club. He might or might not have read about writing itself. One hopes there are more mights than might nots in that particular author's case. Writing is hardly a science, yet it helps to know how it works, what to do and what not to do, how to build plot and character development.

The "writer first, scientist second" is a generalist. His fascination starts with people (read: characters). People are not guided by rigid, inviolable laws. The scientific fields that study people are so-called "inexact sciences" because, while they might predict behavioral tendencies, they can never predict exactly what, given a specific input, the specific output will be. But to understand people one must have at least a small working knowledge not only of sociology and psychology (even if it is merely an intuitive understanding) but also have some idea of how history, politics, and economy work. When writing speculative fiction of any kind, those are fundamental for world-building: those authors don't have a ready-made one or the easy shortcuts it implies. If the author wants to write SF, he also needs some knowledge in biology and Newtonian physics, with some quantum mechanics and relativism thrown in, some added astronomy and astrophysics, the whole peppered with aerospace engineering. Research will certainly be limited, and not only limited but dated. The "rounding error" will fluctuate wildly depending on which scientific field interests the author more.

The most successful SF authors of course, belong to the second group. While there has been some very good hard SF written by scientists, the author obviously took some shortcuts with the science (maybe even in his own field, and most likely in fields not his own), and they were also good writers, who understood writing as a craft and a skill set that had to be researched and learned as surely as their chosen field. But they are the exception, not the rule.

SF then will always be considerably softer than science, even Hard SF will be. However, the science of a story will, and must be, subservient to the story. We don't want to read of the trials and tribulations of an electron in the 1s^2 orbital around a nucleus of U 238 in the atomic bomb for an Orion Drive ship that is about to detonate. We want to know what goes on in the mind of the guy at the other end who is wondering what he is doing strapped to a ship that is going to be hit by an atomic bomb.

The level of hardness does not dictate the quality of the work, it merely aids in creating the suspension of disbelief and reassuring the reader that the writer knows what he is talking about, nothing more.

Science does not make a story. People make stories.

It looks as if everyone has a slightly different definition of hard SF - Sabersonic's being tougher than mine. I'm not sure 'The Cold Equations' is even quite hard SF, since it blows off the procedures you'd expect in that setting. (How and where did the girl hide in such a stringently mass limited vehicle?) 'Hard horror,' perhaps?

I tend to define hard SF in terms of the setting, not the plot; i.e., the plot can be character-centric, but the story still qualifies as hard SF if the setting avoids technomagic.

YMMV, and I admit to some ambiguity. By my definition a story could qualify as hard SF while saying practical nothing about the scientific/tech aspects of its setting, so long as the little it did say is plausible, e.g. waiting for the travel window to go to Mars.

All of this said, there is indeed a techno-porn element in much hard SF, as in technothrillers.

So now at Sabersonic's local chainstore the SF/F section is simply F? I guess that is sort of like changing the spelling of the 'SyFi' network, supposedly not to scare off women. (Yes, sexism is alive and well at the networks, and apparently some bookstores.)

Ian - You reminded me of this link that I forgot to include - I've also used the magic of the edit button to retrofit it to the post. :-)

Jean - In a nutshell, yes. (Hence my perhaps generous definition of hard SF!) Truth to be told, IMHO, Realistic [TM] science and tech, used properly, are essentially flavoring, and part of the sleight of hand that goes into the famous willing suspension of disbelief. Like convincing swordplay, or knowing something about Navajos if they show up in a Western.

I think that you might be giving too much credit to 'current theory' when it comes to hard sci fi. Everything with think we know about deep space comes from our perceptions from within our gravity well. What do we really know about how gravity works? Yes, we have some mathematical models that predict the effects of gravity, but we don't really know how it works.

If you want really hard sci fi, you need to make the current assumptions by current theory, and then discover at a very catastrophic time, that those assumptions don't apply in all situations.

Rick - She hid in the broom closet. She wasn't noticed because if she had been found (Say, during a simple pre-flight inspection that you would expect on a no margin for error craft) the author wouldn't have been able to lecture us about The World Is A Hard Place And You're All A Bunch Of Fools For Thinking Otherwise.

Lousy engineering, an idiot-plot, and a big ol' bumper sticker saying 'Writer On Board'. I'm not a fan.

Ian_M

To Rick: Actually, I meant to say that the only stories I myself have read that is remotely considered Hard were "The Cold Equations" and "Starship Troopers". Sorry for the misconseption. *Knocks on own skull* Dumb, dumb.

Though the arguments on Hard SF being dated in a few years is an interesting point. Especially in the technical matters of how a particular piece of technology or physics phenomenon is explained to the reader such as the one example given on Atomic Rockets where what sounded like a modern cell phone for a book written in the early to mid twentieth century and the illusion is destroyed when the hero of the story pulls out the wax disk. The suspension of disbelief and plausibility can be easily destroyed if the technology described betrays the decade to which it was written. It would appear that the more technical and accurate the technology and science used in the book, the less standing power it has over time compared to more softer SF whose technology is either littered with technobable that would give Star Trek a run for its money or the actual workings are so obscure and briefly mentioned that they hold decades after they're written if only because fans of the story are still trying to explain in plausible scientific theories as to how ti all works out.

Hard Sci-Fi as we know it is a trick upon itself, a very difficult trick that only a few have mastered that balances technical plausibility with plot and characters that one can understand and relate to. A balance that becomes an enjoyable read. The Author is either too technical and the book shows its age in only scant years since its publication, or knows enough about story telling that it keeps the suspension of disbelief that is kept taunt decades or more since it is first put to paper but with the scientific accuracy of a fifth grader with an all F report card if one looks at it hard enough.

- Sabersonic

Ian - Now I can come out of the closet as a non-fan too. 'The Cold Equations' is a chain jerker, manipulating the reader. It is like having the bad guy stomp a kitten just so we know he's baaaaad.

Sabersonic - One thing that quickly dates a lot of hard SF is the Fad of the Decade, which by next decade is likely passé. I suspect elevators might fall into that category, and I'm pretty near sure that magico-nanotech will.

In contrast, much of Clarke and 50s vintage Heinlein stands up well, including Starship Troopers (IMHO one of the last good books he wrote; starting to show his later bad habits but not overwhelmed by them).

Heinlein's Between Planets starts with a kid on horseback answering his phone. Heinlein makes no special deal about it, and the reader today would think nothing of it ... but of course would miss how it read in the 50s and 60s.

Back in the 70's the Space Elevator concept might have looked like a 'Fad of the Decade.' But fascination with the idea persisted into the 80's, surged in the 90's when the discovery of buckytubes made it look more plausible than ever, and refuses to go away in the 00's. If SF authors continue playing with the idea for a few more years, it'll enter its fifth decade. When does this stop being a fad?

Rt

"Now I can come out of the closet as a non-fan too. 'The Cold Equations' is a chain jerker, manipulating the reader. It is like having the bad guy stomp a kitten just so we know he's baaaaad"

I can't comment on 'The Cold Equations'. However, don't all stories manipulate the reader to some degree? Is it a matter of heavy-handedness / obviousness (like the kitten-stomper, or in one novel I read of the Roman invasion of Britain, the Emperor Claudius stopping to gloat after his elephant had trodden on a little girl), or am I missing something?

Carla - The Cold Equations is a particularly heavy-handed short story. All stories manipulate the reader, but this one is downright Spielbergian in its unsubtle yanking of the reader's chain. And the plot requires that all the people in the story be fools.

- The stowaway, who sneaks aboard an emergency medical craft because she wants to visit her brother in the colonies.

- The pilot and 'ground crew', who don't do a full inspection of the ship before takeoff despite the fact that the craft is designed with absolutely no margin for error.

- The engineers, who designed the craft with absolutely no margin for error but left in an unneeded storage closet for stowaways to hide in.

- The unmentioned emergency planners, who decided to deliver the everyone-dies-if-they-don't-get-it medicine by the futuristic equivalent of a dogsled outfitted by the Scott Expedition.

- The pilot, for throwing the girl out the airlock rather than, say, his chair and bunk.

I'm all for stories that show people forced into making hard choices. But in this case the characters were railroaded into the editor's* preferred fate.

* I checked and it looks like John W. Campbell demanded that the writer, Tom Godwin, change the ending so the girl died. That makes a certain amount of sense. People were always disposable in Campbell's vision of the future.

Ian_M

Roadtripper - I don't recall elevators from (most of) the 70s, though I'm sure the idea was around. I first encountered it in Clarke's Fountains of Paradise, which I see dates to 1979. But my impression is that it only became a fashionable SF and space-geek trope well into the 90s.

That said, it's a fair point that after some point particular ideas cease to be fads and become more or less permanent tropes.

Carla - Well, yeah, all fiction manipulates the reader. I suppose I'm speaking of heavy-handedness, as in the example you give about Claudius. (Really, of the Julio-Claudian emperors he seems one of the least likely to gloat in that particular way. Nero or Caligula, on the other hand ...)

Ian - I hadn't even thought of some of the points you make! But yeah, I hate plots that depend on stupidity, especially on the part of the hero.

I walked out of the movie 'Rob Roy.' First Our Hero sends his friend riding across the 18th century Highlands, at night, after letting everyone know the friend is carrying a bag of gold coins. Then, he leaves wife Jessica Lange (and their children) unprotected, because of course no one would ever imagine that the 18th century English might attack by boat.

Two strikes and I'm out! :-)

Oh, if we're going on to rants about bad scifi, let me bring up the recent TV movie Meteor. Ugg... The initial premise, while conceivable, completely ignored the reasonable travel time from the asteroid belt to Earth. Synopsis: Comet hits a huge asteroid in the belt and it heads for Earth. The 'heralds' show up within 24 hours of impact and the big rock is due in less than 48. I'm sure there was some sort of drama where everyone tries to make peace with their lives and all that, but I couldn't get by that huge gaff. If they had simply used months instead of days, I probably could have watched it. But there is no way anything could survive the momentum transfer that would drive a rock from the asteroid belt to Earth in 48 hours.

Wow, a meteor going 1000 km/s plus - now that's impressive!

It doesn't even make sense from dramatic perspective. A few months would be just the thing to get a little soap opera going, but I guess they wanted to cut to the chase.

They could have even shown the event in space and then cut ahead several months where the astronomer develops the theory of the missing asteroid and only just spots the incoming meteor with a few days left in the trip. There's just so many ways they could have done things that would have made more sense...

OK, I'm going to forget about it now, or it will just keep eating away at me.

Ian_M - Thank you for the potted summary :-) It sounds absolutely dire.

Rick - Ah, yes, that Rob Roy film. A fine example of the Braveheart school of film-making.

Carla - Apparently it isn't Sir Walter Scott's fault, either - according to Wikipedia, at least, the movie was not based on his book.

"That said, the, um, hard truth is that even most of hard SF is, in its heart of hearts, space opera. My posts on space warfare are the most popular I've done on this blog, and probably are what brought a good many of you here. From a Realistic [TM] perspective, space armadas or 'constellations' are none too likely – it is indicative that even though the Space Age began amid superpower rivalry and continued that way for a generation, neither side ever found reason to build and deploy space warcraft. But it makes for cool space opera."

I have to agree! people want just so much realisim in a story...after all, we read any fiction to fire up our imagination not (usually) to increase our store of knowledge.

Ferrell

There are two motivations for 'realism' in SF. A secondary one is to describe how things might plausibly happen in the future - but for every hit that SF writers have scored, they've had many and often entertaining misses. (Which after all is largely what has given rise to steampunk, and possibly rocketpunk.

But by far the main purpose of 'realism' is as an aid to fakery, to help sustain the willing suspension of disbelief.

every time I remember "the cold equations" I think of another way she could have been saved. And I remember my english teacher going on about how it was an example of "good sci-fi". urgh. (even if everything was bolted down, they could have released her weight in air!)

-Mark

I think there are two schools of thought for that: Wizard of Oz and James Bond.

The Oz model uses real examples of physics as a smokescreen so that you don't notice that magic is going on behind the curtain. The distraction is usually enough unless someone pulls back the curtain.

The James Bond model comes right out in the first scene with something so far out there that the rest of the story is plausible by comparison. It grabs the audience at the start when they are most willing and sets the stage. This also works for the "How did I get into this mess?" stories which start at some ridiculous point in the story and then flash back and build up the suspension through a series of events.

On a different note, I'll point out again that 'hard scifi' is really just current theory. It is inherently murky because we really don't have the perfect understanding of the universe that an author needs. I think internal consistency is more important. Avoid the unintended consequences. I can accept a setting with reactionless drives, but if that setting doesn't also have relativistic weapons (putting said drive on an asteroid) then the suspension of disbelief fails. So physics defying technology needs to play an important part of the story, or you're just better off not having it.

Mark - They did, when they opened the airlock to space her.

Ian_M

Wouldn't it have already been too late to eject her? You need a certain speed by the time your booster rockets give up. If you don't have it, you don't have it. Ejecting someone after that isn't going to make you go any faster. Basically, you've already missed your window and should abort the mission because it cannot be salvaged. At that point you should be trying to rescue both lives.

In order to make up the lost velocity, you'd have to eject her at like mach 7 or something ridiculously fast.

Now if he was on some sort of ion drive or high Isp low thrust system, then her mass might affect things. But that means a long duration trip and there's no way they'd put a person on that trip and cut things that close. If they did that sort of thing, then it was designed by the ground crew as a one way trip with no intention of letting the pilot survive. At that point, the girl probably wasn't 'accidentally missed' but was intentionally placed there to sabotage the mission... and she probably knew too much as well. Obviously, it is a case of the aerospace manufacturer making promises that it couldn't keep and used the girl as an excuse to buy time.

Citizen Joe: If I remember the story correctly, it wasn't that the ship wasn't fast enough to reach it's target destination due to the existence of a stow away. Rather the problem is the slowing down part. The thing is (suppose to be) designed and fueled only to have enough DeltaV to get to its destination and land safely.

Though then again, if enough people in the future did read the story, it'll be a lesson of what NOT to do before an emergency launch on a craft to haul only so many kilograms of mass besides the craft's own and propellant.

- Sabersonic

It still sounds like he was set up for failure. When you put a man's life on the line by flying a plane or piloting a space ship, you must account for inevitable problems. Airplanes fly with more fuel than they need. Often this extra fuel means that their landing gear can't handle the landing. So, once they get close, the either dump fuel or run dirty to burn off the excess. Proper landing should involve attaining an orbit (sircraft placed in holding pattern), getting appropriate landing instructions (clearance from the tower), and then finally coming in for the landing. If you don't have enough play to deal with a hundred pound kid, then you shouldn't have been sent out there manned. Again I say that that pilot was never intended to survive and the kid was planted there on purpose. It actually sounds more like a Kobiyashi Maru scenario from Star Trek.

Citizen Joe, I used to think the ground crew and mission planners were sadists. Now I think they're producers for a reality TV show.

Survivor: Starship! Now with exterior cameras!

Ian_M

I have a theory about 'The Cold Equations.' People who come from a literature/humanities background (and who are often rather intimidated by math anyway) accept the premise as given and therefore are moved by the story.

People with a science or engineering background (or simply interested in those things), on the other hand, immediately try to figure out how to save the girl - and they more they consider it, the more holes they find in the plot.

Anon - I'll argue that the James Bond model works better in film than books, because you can't so easily go back to examine possible plot holes. Even in the DVD era, you can't go back while watching in the theater, and probably don't go back the first time you watch it on DVD.

That said, yes, 'realism' can only embrace current theory, which is almost certainly not the Last Word. On the other hand, new theories usually don't invalidate earlier ones under 'normal' conditions. We still use Newton to analyse orbits, and for that matter most terrestrial motion is effectively Aristotelian - if your car runs out of gas, it stops; it doesn't coast indefinitely on in the direction it was going. :-)

As an aside, I wonder if you caught Virtuality a few weeks back. I was really very pleased, both at the drama, and at the science, which, seeing as it was good, had rockets, and was on Fox, entailed it was doomed. But no space shootouts at all, a ship with a gimballed centrifuge and an Orion drive on an appropriately long journey to a real star, with attention paid to how they can pass the time (even got the time dilation math right.) Makes for a pleasant two hours of SF harder than you can usually find in visual mediums.

Alas, I wasn't even aware of it!

Post a Comment