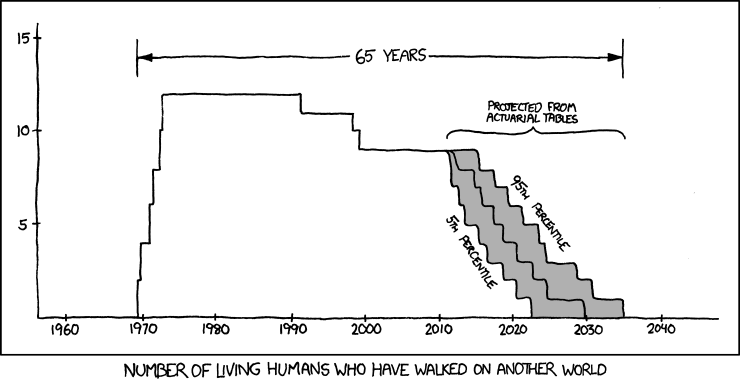

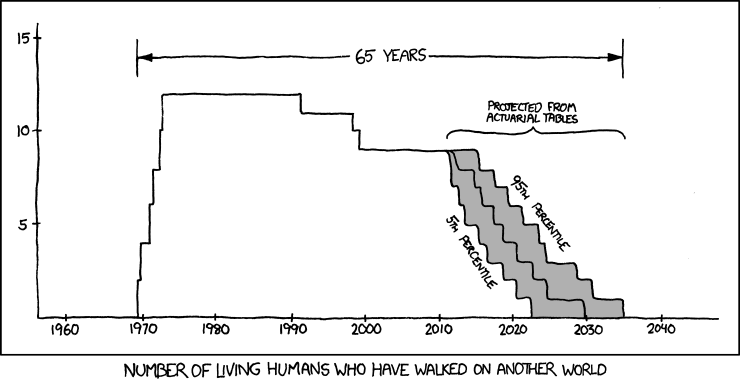

Click to the original at xkcd to view the mouseover. Thanks to Winch of Atomic Rockets for the tipoff; he is not to blame for my (somewhat belated!) use of it.

This post is, obviously, political. You have been warned. But the political content is not gratuitous. There are plenty of places online where people whom I generally agree with bash on people I generally don't. (See his blogroll, which is actually fairly eclectic.) That is not my objective here. The remarks that follow are specific to the themes of Rocketpunk Manifesto.

I should also note, for a rather international readership, that I am using 'liberalism' in its 'Murrican sense of center-left, not the much more inclusive sense it has in political philosophy (let alone the center-right connotation that it has in some countries). And the entire post is parochial to the extent that it deals specifically with 'Murrican spaceflight. But only three countries have launched people into space; only two on a substantial scale, and I am conversant with the political culture of one of those.

The leading frustration in space geekdom is that while we have accomplished quite a lot in space, we have not gotten as far in space as we hoped, or people 40 years ago took for granted. 2001: A Space Odyssey remains the benchmark of our imagined space present - an alternate world of regular scheduled spaceflights, Moon bases, and human missions to Jupiter. It is the classic rocketpunk vision, with surprisingly little Zeerust.

It did not happen that way, and the basic reason is pretty damn simple: NASA's budget was cut. Reductions from the Apollo era peak were pretty much a given: Apollo was a rush effort to overtake and beat the Russians. That is why, for example, 'Moon Direct' was chosen over the traditional rocketpunk architecture of a shuttle and station first, then moonships.

The amount of cutting, however, was dramatic. NASA's budget peaked in 1965 at $33.5 billion (in equivalent 2007 dollars). By 1969, with Apollo up and running, the budget was down to $21.4 billion. By $1975 it was down to $11.1 billion, and stayed below $12 billion per year until 1983. After that, as the Shuttle entered service, the NASA budget rose modestly, and from 1987 through 2008 (the last year reported), it has ranged between about $15 and $20 billion, averaging $16.4 billion.

The NASA budget dark ages of the 1970s and early 80s were not without consequences, since this was the era when the Shuttle was developed. Richard Nixon reportedly regarded the space program as a 'Democratic boondoggle.' The expression is noteworthy, but his deeds mattered more than his words. He did not cancel the Shuttle program, but he forced a reluctant US Air Force to fund part of its development - in turn for which the Shuttle had to be designed for much larger payloads than originally intended.

What in earlier design iterations had been a sort of space minivan became the familiar space truck - and the combination of a larger payload and smaller development budget forced a fundamental design compromise. What had been intended as a fully reusable liquid fuel TSTO became only partly reusable, and dependent on solid fueled boosters.

We do not know how the Shuttle would have performed if built as originally conceived. There is a serious argument - I have at times endorsed it - that robust reusable orbiters are simply beyond our techlevel: Getting to orbit at all requires an extreme design, and returning in one piece (or even two pieces, for a TSTO) makes for an even more extreme design. You end up not with a truck or minivan, but the equivalent of a racing car that must be torn down and rebuilt before it returns to the track.

On the other hand, the experience of the Shuttle, and its various canceled would-be successors, may simply prove that you get what you pay for, and a severely compromised design is liable to deliver compromised performance.

The Shuttle, in fact, has performed remarkably well given its conceptual shortcomings - a heavy lifter, designed for an entirely new operational realm, but with no development prototype fully tested in advance of the operational vehicles. Its two catastrophic losses were both due primarily to operational failures, not its design shortcomings. Perhaps even more to the point, the design flaws implicated in both losses - the combination of SRBs and external tank for Challenger, and the external tank insulation for Columbia, - were both consequences of the Nixon-era design compromises, not part of the original TSTO conception.

What, you may fairly ask at this point, do particular decisions of a single president 40 years ago have to do with broader political philosophy? The significance is that Nixon's time in office is when the momentum of US political culture shifted against 'big government' and public sector initiatives, of which the space program was the iconic representative.

The downgrading of the Shuttle program thus turned out to be part of a larger political shift, which has affected American space activity ever since. NASA had, and retains, a sufficient base of public and interest-group support that, like Amtrak, it could never be eliminated outright, but it has been kept on a sort of starvation diet, the root cause of many of its failings. If you provide just enough funding to keep a program from dying outright, you keep it alive but ensure that it will be suboptimal.

At the same time an enormous amount of wishful thinking - but not so much actual money - has been invested in the idea that somehow the private marketplace would come to the rescue. But no one has yet managed to come up with the McGuffinite that would tempt big capital to write big checks.

Yes, we now have SpaceX, and may soon have Virgin Galactic, and more power to them both. But let us put them both in perspective. SpaceX aims to tweak and streamline some operational processes within the existing state of the art. It is not remotely an orbit lift game changer. And Virgin Galactic is all about selling the sizzle, not the steak. The sizzle is pretty cool - if I had $200 K to burn, I'd happily buy a ticket for five minutes at the inner edge of space. But the kinetic energy involved is only a few percent of that needed to reach orbit, and orbit is the starting point for space travel in the sense discussed on this blog.

It is always possible that this might change tomorrow - that some McGuffinite will turn up (or at least be strongly enough believed in) that the capital markets will pony up the trillion dollars or thereabouts down payment on the human Solar System. But the smart money has never yet bet that way.

The stall-out of space travel coincides both in time and functionally with the rise to predominance of libertarian economic attitudes. The irony is striking, because 'Murrican space-mindedness has deep and long connections with libertarianism, going back at least to Robert Heinlein.

It has been noted here and elsewhere that the ethos of rugged individualism associated with libertarianism is (absent some major magitech) a poor fit for the requirements of living in space. It also turns out to be a poor fit for getting there.

No, I don't expect anyone to leap up onto the stage, throw away their crutches, and proclaim that they have been healed! People adopt political philosophies for varied and complex reasons, and for that matter everything is not about space. I am merely noting that if, as a matter of principle, you rely on the private marketplace for nearly everything, don't hold your breath waiting for it to provide extensive space travel.

Standard provisos apply. The discussion above is focused on human space travel, but there is an argument to be made - I have sometimes made it - that going in person is nearly irrelevant to, or even a distraction from exploring space. In spite of xkcd, our robotic probes have opened up the Solar System to an extent no one in the rocketpunk era ever imagined.

Other provisos. It is certainly no automatic given that, had the liberal project continued through the last 40 years, it would have necessarily included a vigorous space program. The Space Race might have ended anyway once a touchdown was scored. And a significant segment of the 'Murrican liberal coalition has - at least since the 1960s - shown a marked, Thoreau-esque distaste for big noisy things that go fast.

It is also arguable that other strands of the 'Murrican right are not necessarily so unfriendly toward large public initiatives. 'National greatness conservatism,' of the sort sometimes championed by neoconservatives at the Weekly Standard, might well be open to a major space effort. Indeed, rhetoric along those lines accompanied the GW Bush administration's talk of going to Mars, which produced 'Constellation.' The rhetoric, alas, was not accompanied by funding, and ended up leaving NASA in a very awkward spot.

Once again, you get what you pay for. And to the degree that we wish society to consider space travel - human or robotic - profoundly important, I will argue that we must at least consider whether society, through a public initiative, needs to step up and pay for it.

It is tempting at this point to say "Okay - let's rrrrumble!" But as always in these comment threads, light is more useful than heat.

So I will merely say: Discuss.

(The Saturn V launch image is from NASA.)

In the United States this is Memorial Day, a holiday that arose from the American Civil War. The day that elsewhere in the Anglosphere is Remembrance Day is Veterans' Day here, and less somber. Most countries surely have some equivalent holiday. Previously on this blog I have noted it simply by recording the then-current death tolls from the wars the US is fighting.

In the United States this is Memorial Day, a holiday that arose from the American Civil War. The day that elsewhere in the Anglosphere is Remembrance Day is Veterans' Day here, and less somber. Most countries surely have some equivalent holiday. Previously on this blog I have noted it simply by recording the then-current death tolls from the wars the US is fighting.