The March of Time

Time, as I have noted previously on this blog, is nature's way of keeping everything from happening all at once. Time is also what got away from me last week, which is why I'm posting this 'I'm still here!' message instead of a full length post.

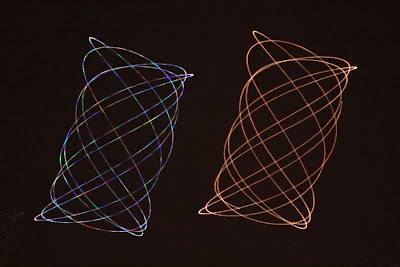

The time lapse image, from Astronomy Picture of the Day, shows Mars and the star Regulus close together in the sky, and close to the same apparently brightness. The telescope was deliberately jiggled to get this pattern, which shows the scintillating ('twinkling') effect on the atmosphere on light sources of very small angular dimensions.

Also from APOD, this impressive - and a bit sobering - X-ray image of the remnant from Tycho's supernova of 1572.

Consider this an open thread.

67 comments:

We've disgussed, argued, and pondered time on this blog; is time travel possible? is it even wise to attempt? We've talked about FTL leading to time travel; whether it was self-defeating or if it permissible. My personal opininon is that only trips back that CANNOT change anything would be permitted. That may be part of the solution to the Fermi Paradox- civilizations that are capable of comming out to meet us are too afraid to do so.

Ferrell

Ferrell:

"My personal opininon is that only trips back that CANNOT change anything would be permitted."

It is impossible for a trip to the past to not change anything. As soon as you're in a particular spacetime coordinate, you will affect everything in that coordinate's future light cone. Even a bent blade of grass will have consequences.

You might argue about whether or not you accept the chaos theory notion that it would be a big change, but that is besides the point, because it would be a change, which is still enough to break physics as we know it.

To preserve causality, you need to either not have FTL, or you need a special frame of reference so that while people can travel back in time according to other frames, they can never travel back in time according to the special frame. At most, you could have a "manually-built" special frame, a la the frame of a wormhole network.

Just a thought, but people are always talking about the heat requirements of lasers. I know most want solid state or free electron lasers, but I am wondering if a chemical laser might havs some advantages. I mean couldn't you vent the gas created by the laser, that would reduce the radiator size needed while still having a very powerful laser

Ferrell: Trips back in time that could change things (on the timeline you left from) are definitely paradox-inducing, and thus impossible. Either backward time-travel is utterly forbidden, or time works much differently than we imagine. Another solution to the Fermi Paradox is that alien civlizations do exist, but not in the same time stream (or whatever) as us. Maybe they started in the universe/timeline as we perceive it, then invented FTL/time machines and ended up somewhere/when else entirely.

Anyway, regarding whether time travel is possible, I'm going to simply invoke the Fermi paradox: where are all the time travellers? Except this time it isn't a paradox, because a priori, time travel being impossible is far more likely than us being the only sentient species in the galaxy.

While they might be convenient for telling storytelling, I don't buy into "time travellers are here but they're all staying incognito" explanations.

So that leaves the "time travel is impossible" explanation, or the "time travel can only go back until the construction time of the first time machine" explanation. In the latter case, whoever builds the first time machine had better prepare for a lot of tourists...

Anonymous:

"Just a thought, but people are always talking about the heat requirements of lasers."

Right now, from the looks of things, your power plant will generate more waste heat than the laser.

Time travel probably takes you to a parallel universe where (say) Hitler really was assassinated (by you), only now you are stuck in that reality; as far as anyone can tell in this universe you simply vanished.

Tim and anonymous, my response to the paradox issue is that it does not make time travel impossible. The paradox would only be in the human mind.

We've all heard it before, right? In the grandfather paradox, there are several possiblities: it creates an alternate timeline/universe, which only you can observe (the people from your original timeline don't know it has happened); it causes you to cease to exist, thus resolving the paradox; time travel which could possibly result in this is impossible.

The final possibility is one that I dismiss, because it assumes that what man thinks is logical necessarily determines natural law.

Personally I think time travel is impossible, not because of paradoxes, but because the past no longer exists.

As far as Fermi's Paradox, that is to say, why have we not been visited by aliens, I think all it indicates is that the speed of light is in fact a barrier. I hope that's not true, because it limits where we can go in a reasonable time (although we could go to a star in 4 years ship time, traveling at 99% the speed of light, but by reasonable I mean a few days or so). It could mean that the aliens do not want to interfere with our culture (Prime Directive) or that we're in a nature preserve or something... :)

--Brian/neutrino78x

Regarding Fermi's paradox: A possibility that seems often overlooked is the possibility that aliens that have the means simply aren't interested in us and/or cannot bring themselves down to our level to communicate.

For example: Let's take an ant colony built in the cracks between pavement blocks. As far as the ants are concerned, they are the only form of sentient life on their chunk of sidewalk. We humans, who are positively god-like in comparison, are incapable of communicating anything other than hostile intent to the ants (as we can simply destroy the colony with one stamp of our feet), and the ants do not have sufficient intelligence to communicate with us. The ants can detect evidence of our existence, but because we are beyond their comprehension they don't attribute that evidence to the existence of sentient life elsewhere.

So, perhaps supernovae, background microwave radiation and gamma ray bursts are actually indicative of sentient life elsewhere in the universe, they're just so immensely powerful that we cannot consider their actions as anything other than an elemental force of nature (this also opens up the argument that the universe itself is a hyper-sentient omni-organism, but one thing at a time, okay?).

The Other Anonymous said:"Just a thought, but people are always talking about the heat requirements of lasers. I know most want solid state or free electron lasers, but I am wondering if a chemical laser might havs some advantages. I mean couldn't you vent the gas created by the laser, that would reduce the radiator size needed while still having a very powerful laser"

That's called 'open cycle cooling'

and it was the prefered method of laser cooling for the 1980's SDI program space-based lasers.

Ferrell

The Fermi Paradox could simply be explained by there being an average of only one civilization per gallaxy at any one time. In other words, distance; even if FTL is possible, intergallactic travel might be just too far...but having an entire gallaxy to yourself might be enough for most civilizations.

Ferrell

Thucydides:

"Time travel probably takes you to a parallel universe where (say) Hitler really was assassinated (by you), only now you are stuck in that reality; as far as anyone can tell in this universe you simply vanished."

Parallel universe time travel might be more convenient in terms of avoiding paradoxes, but the laws of spacetime as we currently understand them don't support it. Quantum mechanics is more friendly to the idea of parallel universes than relativity, but I have no idea what quantum mechanics says about time travel.

Brian/neutrino78x:

"In the grandfather paradox, there are several possiblities: [...] it causes you to cease to exist, thus resolving the paradox"

No, you don't cease to exist. You simply never did exist and never will. Your grandfather died in a completely unrelated, completely plausible car accident that does not require your interference to take place.

The only people who will not be preemptively forbidden from existing in some similar manner, are the ones who are not stupid enough to attempt to murder their own grandfathers.

"[...] time travel which could possibly result in this is impossible"

Which is all time travel.

"The final possibility is one that I dismiss, because it assumes that what man thinks is logical necessarily determines natural law."

The important thing here is that you should not expect key events to happen as what a human perceive to be pivotal moments. For example, if you try to go back in time to kill Hitler, do not expect the plan to work perfectly until the moment you fire the gun, at which point it jams. This suggests that the jamming is a "result" of you performing an action that would violate causality. But time travel is involved, so causality is per definition broken - consequences won't neatly happen after the event which caused them!

"Personally I think time travel is impossible, not because of paradoxes, but because the past no longer exists."

Watch your language. You said "no longer". Why should time travel be held back by something "no longer" existing? Just travel back in time to when it did exist. Oh wait...

Anyway, remember special relativity. In special relativity, there is no universal unambiguous definition of "now". If a star 1000 lightyears from here is currently going supernova according to our frame of reference, then there are other frames of reference according to which the star has already gone supernova long before I type this, or will only go supernova long after I type this. So the star might or might not "no longer" exist.

Spacetime as seen in relativity is much more friendly to the view of eternalism. (Also note that an eternalist philosophy in no way implies that time travel is possible, although it does suggest that if time travel is possible, then it's probably of the "you already changed the past" type.)

Mangaka2170:

"A possibility that seems often overlooked is the possibility that aliens that have the means simply aren't interested in us and/or cannot bring themselves down to our level to communicate."

This might be the case if you take the "apes or angels" argument to its logical conclusion - suggesting that after developing technological civilization, it is a relatively short time before a species advances to the point where it's so far ahead of us that it would not deign to talk to us any more than we would deign to talk to a flatworm. (To clarify, I'm saying this because humans probably evolved from worm-like creatures, having diverged shortly before the Cambrian explosion. Yet we rarely feel any kinship to the modern animals that are supposedly similar to our ancestors...)

"The ants can detect evidence of our existence, but because we are beyond their comprehension they don't attribute that evidence to the existence of sentient life elsewhere."

Are you sure about that, though? Ants might not be able to notice and appreciate the things that we value in ourselves as sentience, but ants might still have the means to determine that we are at least as smart as themselves. From our point of view, we're completely unable to communicate with them, but from their point of view, they might not feel anything is amiss, because their communication with other ants is also very primitive compared to what we are used to.

But I can't help but notice that even if from an ants' point of view we're doing just fine at "communicating" with them, our messages are rarely friendly...

Ferrell:

"In other words, distance; even if FTL is possible, intergallactic travel might be just too far...but having an entire gallaxy to yourself might be enough for most civilizations."

If I had FTL travel, the single biggest thing I would wish to accomplish with it would be to meet another sentient species. (Failing that, finding some other planets with non-sentient but post-Cambrian-explosion-analogue biospheres would be the next best thing.) Compared to that, having a galaxy's worth of resources to play with is kind of nice, but is really just a fringe benefit.

Surely, if we are not alone in the universe, there are at least a few other species out there that feel the same way.

A rather odd speculation I read once was aliens who were sufficiently advanced would create basement universes that were tailored to whatever they thought desirable and move in there rather than bothering with a "wild" or uncultivated universe.

If they left the mouth of the basement universe wormhole accessible, maybe we would be able to visit, but they would probably "shut the door" once the basement universe was created and inhabited.

What I find most disheartening about trying to shoehorn my space opera sense of wonder into a hard science rulebook is that when it comes right down to it, there's just no way we're getting to the stars with our current understanding of physics or in our current bodies. The whole notion of folks like us getting on board a ship and going off to another star system to have an adventure on a planet with breathable air and coming back (just) in time for our sweetheart's birthday is nothing more than fantasy. Either there is a radical physics revolution on the horizon, or it will be a LONG time before we get to the stars, and likely not in our current forms. Either way, it makes it really hard to write any kind of plausible interstellar hard SF.

But, hey, I love a challenge.

Thucydides:

"A rather odd speculation I read once was aliens who were sufficiently advanced would create basement universes that were tailored to whatever they thought desirable and move in there rather than bothering with a "wild" or uncultivated universe."

In this case, we will not be able to meet other civilizations in our universe... but if we wished to meet other sentient species, then we will eventually get around to creating our own basement universe and we will be able to design it so as to give rise to other civilizations which we can then contact and/or study.

Now consider the possibility that we alrady live in such a basement universe, and our creators just haven't gotten around to introducing themselves yet...

"Either way, it makes it really hard to write any kind of plausible interstellar hard SF."

There's a solution to this: set your story on a generation ship (or a group of them traveling together, if you want a more dynamic setting).

Another possible answer to the Fermi Paradox, is that the aliens are here, have always been here, but they are simply too different from us to comprehend. Thus we have many UFO/alien/supernatural encounters being reported throughout history, which don't add up into any kind of coherent or believable scenario. The truth may not only be stranger than we imagine, but stranger than we are capable of imagining.

Mangaka: Yes, that certainly is a solution, but not a very exciting one. The appeal of SF (for me) is a wide open galaxy, not the closed interior of a ship. Do you know what I mean?

Tim:

"Another possible answer to the Fermi Paradox, is that the aliens are here, have always been here, but they are simply too different from us to comprehend."

The laws of physics do not exist just for our sake. Other sentient species should not all get to play with their own laws of physics.

Tim said: "Either way, it makes it really hard to write any kind of plausible interstellar hard SF."

Have you read _A Deepness in the Sky_ by Vernor Vinge? That might be the sort of thing you want.

Jim: I read "A Fire Upon The Deep" and liked it, but didn't see what was so "hard" about its science. In that regard, I like Baxter and Reynolds, but even they "cheat" on their physics from time to time.

But as far as I understand physics, you are limited to a "realistic" reaction-based drive that even with an antimatter fuel source is still not quite good enough to get a human crew to another star in a tolerable time frame (if at all). More likely such a drive could get an automated probe or probes out, and little else.

Your other choice is a "magic" drive that uses some as-of-yet undiscovered principle of physics or starts a new branch of science altogether. Even if this is still limited by light speed (or 0.999 of c, let's say) at least we can get somewhere interesting in our own lifetimes, if not that of our families back home... The problem now is the secondary effects of your physics breakthrough. Does this lead to overtly opera-flavored tropes like artificial gravity floors? Force fields? Tractor beams? Anti-gravity cars? If you don't have these things, why not? Because if you do make your technology this powerful, you've reduced the human factor to a miniscule proportion, I would think. Now add FTL, and you've got an even bigger can of worms you've just opened up. Now you're playing with literal god-like levels of power, and to do what? Epic space dogfighting? Mining for rare elements? Space pirating/policing?

Tim: while _A Fire Upon the Deep_ has FTL etc. _A Deepness in the Sky_ is set in the 'Slow Zone' where physics is as we currently understand it, so all travel & communication is light speed or slower.

The more time that passes, the more quaint stories become. Verne wrote a story called "The Sleeper Awakes" about a man that falls into a suspened-animation-like coma for 100 years. The things that the story got right, and the things it got wrong, are more interesting than the story itself; calling for home delivery (right), listening to music over telephone lines from a central broadcast studio (wrong and right), or that fashions would be Victorian (oh, so very wrong...). Just like in real life, we can't be completely sure about how details in our stories will be viewed by readers decades from now. We all hope that at least the story remains entertaining enough so that the reader ignores the things we got wrong.

Ferrell

Milo:

Parallel universe time travel might be more convenient in terms of avoiding paradoxes, but the laws of spacetime as we currently understand them don't support it.

It is possible that space-time could take on a "non-Hausdorff" geometry. In very basic terms, and playing fast and loose with the terminology, this is where your space part of space-time bifurcates into two different spaces past a certain time. In other words, you get parallel universes. There is no evidence one way or the other about whether space-time is Hausdorff or not.

Speaking of time, and since splitting a time-line into parallel universes has already been brought up (both via the many worlds interpretation of quantum mechanics and via non-Hausdorff geometries in relativity), I thought I'd mention a little-realized consequence of this - two separate "parallel universe" time-lines can merge into one. This can only happen when both time-lines end up giving indistinguishable physical "present times", but events of the present will have multiple possible paths. Extending this to the many worlds interpretation of quantum mechanics, not only does every possible future happen, but every possible past already did happen.

Personally I'm fond of the many-worlds interpretation of Time Travel. Each plank-second of time random events lead to divergences in the timeline. Moving backwards in time and changing these divergences simply moves the timeline into a new direction.

One of the amusing notions me and my friends came up with was if you could create a point of divergence early on enough, like... near the beginning of the big-bang, you might cause the universe and the very laws of physics to unfold differently. Which would get you alternate universes with alternate laws of physics, maybe things that look like magic.

Probably not very plausible, all in all, but I still like the notion for story-telling purposes.

I'm not sure why so much ink has been spilled ove r time travel paradoxes. It should be obvious that if an observer can travel back in time and interact with an earlier age, then all of the effects of that interaction were accounted for in the series of events that led up to his being able to travel back in time. This leads to one of two conclusions -- either time travel is for some reason impossible, because we don't see the effects of time travelers, or time travelers have as of yet not had very much effect. (This could either be through choice or through accident.)

WRT operatic futures being implausible, I'm just not seeing that either. A modern nuclear aircraft carrier generates as much energy per unit of time as was harnessed by all human machines all over the world 1600 years ago. It is still used by recognizable humans for recognizably human pursuits. If humans put even vaster energies to use, it may mean that accidents or acts of war become unprecedentedly destructive and lethal -- as a 2000 lb bomb, delivered by a jet fighter is, compared to a 32 pound black powder cannon -- but one can still imagine those energies being directed by humans, for human purposes.

correction:

In my previous post, "1600 years ago" was meant to say "in the year 1600".

Welcome (perhaps!) to a new commenter!

A gentle request for 'anonymous' commenters to sign a name or handle, precisely to avoid the awkward 'Other Anonymous' situation!

My - very limited! - understanding is that some kinds of 'travel into the past' are possible without any paradoxes arising. It is only travel into your own past that makes things complicated.

On the Fermi paradox ... I dunno. The best I can venture is that interstellar travel is difficult and intelligent races rare, with the values of 'difficult' and 'rare' being fairly indeterminate.

To be honest, if FTL is impossible that explains a lot. STL travel is difficult, and if planets suitable for colonization are scarce, even the occasional colonial expansion may peter out

Rick: "To be honest, if FTL is impossible that explains a lot. STL travel is difficult, and if planets suitable for colonization are scarce, even the occasional colonial expansion may peter out"

That's what I'm afraid of. And if our understanding of physics is more or less complete, then all of the above statements are the most likely future we can expect.

Of course that doesn't limit what our fictional far future looks like, which is the only one we going to see anyway...

I have always found Niven's reasoning about time travel very convincing -- In a universe where it is possible to travel back and time and change the future by changing the past, time travel will not be invented. The only stable sequence of time is one in which the machine never exists to be prevented.

I've never found the many-worlds hypothesis convincing. Where does the mass-energy to create an infinite number of new universes every second come from?

As to the Fermi Paradox, I have two hypotheses. The first is, how do we know they aren't here? I scoff at UFO sightings because I can imagine a sufficiently advanced civilization would have no trouble creating stealthy means of studying and observing life on Earth. Which one of the dust mites in your bedroom is really an alien robot?

The second hypothesis is how do we know certain "natural" phenomena aren't the work of intelligence? Odd stars off the main sequence might be the result of tampering by a Kardashev II civilization; odd galaxies could be the work of a type III galactic empire. I'd love to sit down with an astronomer and brainstorm about this.

Cambias:

"Where does the mass-energy to create an infinite number of new universes every second come from?"

Why should conservation of energy be adhered to on a multiversal level?

"I scoff at UFO sightings because I can imagine a sufficiently advanced civilization would have no trouble creating stealthy means of studying and observing life on Earth."

Remember that no matter how advanced you are, you still can't work magic. Human technology, despite our incredible progress compared to prior eras, still relies on massive infrastructure to function. We can make light appear with a simple hand movement, but only if electrical wiring has been installed all through the house's walls and the lightbulb and lightswitch are properly connected.

Now we do manage to miniaturize things to some degree as technology advances, but even then, high-functioning small appliances are reliant on occasionally being plugged into larger infrastructure for recharging.

And remember: despite how advanced we are compared to ants, ants can still see us.

"Which one of the dust mites in your bedroom is really an alien robot?"

There is a simple limit on how much a robot that size can be capable of, because you can't make any of the circuits or components smaller than the width of an atom.

"The second hypothesis is how do we know certain "natural" phenomena aren't the work of intelligence?"

We don't.

The best thing to do here is see if we can explain the phenomena with our known understanding of physics. If computer models suggest that (say) sufficiently heavy stars will go supernova, then that suggests that at least some supernovas are not artificially made.

But if we can't explain a phenomenon naturally, then that doesn't mean there isn't a natural explanation. So how would you convincingly determine that a phenomenon is artificial, short of talking to the aliens who did it and have them say "Yeah, we did it."? (Which could still be a lie, if they're just trying to impress us superstitious primitives...) Perhaps if there is some overly rigid pattern to where/when the events occur. But how do we know what patterns a super-advanced species would care to use? They could be too complicated for us to make sense of.

Cambias: You're assuming (in your first hypothesis) that the aliens would be so interested in us as to try to conceal themselves.

The brothers Strugatsky have an interesting take on that in "Another Roadside Picnic" (made into the movie "Stalker" by Andrei Tarkovsky). In the story (in the movie, not so much) the alien artifacts and mysterious physical properties of their area of visitation "The Zone" are hypothesized to mean many things, but the most convincing answer compares the humans to ants foraging through the scraps and garbage left behind at a picnic.

If you want to apply that to the UFO phenomenon, then the random lights, electromagnetic disruptions, loss of time, and abduction scenarios/hallucinations, could be interpreted as unintended side effects of accidental contact with alien intelligences otherwise invisible, intangible and utterly indifferent to us.

Personally, I scoff at the abduction reports because the aliens are just too similar to ourselves to seem truly alien. If people were consistently reporting starfish or octopus aliens, (or more likely, something even weirder) I'd be a little less skeptical.

I think the idea that "stuff we can't explain = intelligent intervention" has been steadily deprecated over the years. For example, the old galaxy classification convention was based on a steady stated view of cosmic evolution. Now that inflation (of some type) is pretty much accepted, and evidence keeps piling up the galaxies (and larger scale structures) are artifacts of initial density variations, we can explain all of what we see as some step in galactic evolution. Similarly, stellar phenomena that seemed inexplicable just a couple of decades ago are all becoming more and more explicable as consequences of stellar evolution under exceptional circumstances.

Cambias:

I've never found the many-worlds hypothesis convincing. Where does the mass-energy to create an infinite number of new universes every second come from?

You no more need energy to create the new universes in the many worlds interpretation than you need the energy to create a new electron when you put an electron into a superposition of up and down states in a spin-polarized beam experiment, and for the same reason. The various "new universes" are really superpositions of quantum states - the possibilities of how the universe might be - that make up the state vector of the universe. This is just the extrapolation of standard quantum mechanical effects, such as the way that the double slit experiment interference pattern is the result of the superposition of states of the photons going through one or the other slit in the photon's wave vector, or the way that a spin-polarized electron beam becomes a superposition of different polarization orientations when measured along a different axis. In neither case do you need to supply the energy to create new photons or electrons - there are no new photons or electrons, just a set of possibilities of the properties of already existing photons and electrons. The "new universes" would be the same, just possibilities of the same universe expressed as quantum states.

Extending this to the many worlds interpretation of quantum mechanics, not only does every possible future happen, but every possible past already did happen.

This makes my brain hurt. If I am understanding it correctly, both sides in every serious debate about uncertain historical facts are correct: There both was and was not a recognizable Trojan War, a major post-Roman British ruler called Arthur, et al.

This is your universe ... this is your universe on quantum drugs.

Rick:

"If I am understanding it correctly, both sides in every serious debate about uncertain historical facts are correct:"

Only all pasts that are consistent with the current state of the universe exist. If there is any archaeological evidence of a historical event buried in the earth, whether we have already found it or not (or perhaps found it but failed to recognize it for what it is), then a past where that event didn't happen is not consistent.

Of course, you could argue that until we collapse the wave function by observing it, the archaeological evidence is in a quantum superposition of both existing and not existing...

But really, I don't think multiple pasts - if they exist at all - are going to differ by a particularly notable amount.

In the Many Worlds conjecture, any universe only has one past. Every universe, at any given point in time, has all possible futures. So, at t = 0, the original universe had no past and all the possible permutations of cosmic evolution in front of it. Likewise, at this point in time, the universe we occupy has exactly the past that lead to its current state, and all possible permutations of cosmic evolution that are consistent with the current state in front of it.

Tony:

In the Many Worlds conjecture, any universe only has one past.

False. Completely false. In the many worlds interpretation, our universe is a superposition of all possible pasts that lead to the current present. This is basic quantum mechanics, in the same way that a photon falling on a certain phosphor on a screen in the double slit experiment took all possible paths to get to that phosphor.

Mr Schrödinger, can you step into the office for a moment; the vet is having some trouble getting your cat out of the box.....

Luke:

"False. Completely false. In the many worlds interpretation, our universe is a superposition of all possible pasts that lead to the current present. This is basic quantum mechanics, in the same way that a photon falling on a certain phosphor on a screen in the double slit experiment took all possible paths to get to that phosphor.

The many worlds interpretation can best be illustrated by a binary tree.* Each node is a distinct universe, and the creation of each node's descendant nodes is defined by a quantum even. One descendant universe is created by the event having one result, the other descendant universe is caused by the event having the opposite result.

*In a binary tree, each node has two, and exacly two, descendant nodes, so that the root level (r) has one node, level r + 1 has 2 nodes, level r + 2 has 4 nodes, level r + 3 has 8 nodes, etc.

Now, one can imagine any number of ways that various universe lines could converge on the same state at a given time. But each of those states, though mathematically identical, exists in its own, distinct universe. Each of those universes has a mathematically distinct past and a mathematically distinct future.

Now, here's the real mind-screw: It is axiomatic that if each universe will experience all possible futures, then every universe with an identical state at time t will have precisely the same set of futures. IOW, there could be an almost infinite number of universes (certainly an incalculable number) that will experience precisely the same future that our is experiencing, but which we can never really know if they exist.

Tony

The many worlds interpretation can best be illustrated by a binary tree.* Each node is a distinct universe, and the creation of each node's descendant nodes is defined by a quantum even. One descendant universe is created by the event having one result, the other descendant universe is caused by the event having the opposite result.

snip

Now, one can imagine any number of ways that various universe lines could converge on the same state at a given time. But each of those states, though mathematically identical, exists in its own, distinct universe. Each of those universes has a mathematically distinct past and a mathematically distinct future.

I don't know what to say, except that this is fundamentally wrong. This is not the many worlds interpretation of quantum mechanics. It has nothing to do with quantum mechanics. In quantum mechanics, all possible physical paths (i.e., histories) that lead to the same physical outcome all happen simultaneously. I recall there is a good discussion of this in the Feynman Lectures on Physics, if you can find a copy. Alternately, read up on the double slit experiment and the path integral formulation of quantum mechanics. This behavior is necessary to the observed properties of the universe when quantum mechanics comes into play.

Luke:

"I don't know what to say, except that this is fundamentally wrong. This is not the many worlds interpretation of quantum mechanics. It has nothing to do with quantum mechanics. In quantum mechanics, all possible physical paths (i.e., histories) that lead to the same physical outcome all happen simultaneously. I recall there is a good discussion of this in the Feynman Lectures on Physics, if you can find a copy. Alternately, read up on the double slit experiment and the path integral formulation of quantum mechanics. This behavior is necessary to the observed properties of the universe when quantum mechanics comes into play."

We're just talking about two different things. Quantum superposition is a mathematical formalism relevant to quantum probabilities.

The many worlds interpretation is a conjecture about what acutally happens at possible points of divergence in the history of an evolving cosmos. It states that at any point where an event can go one way or the other, the wave funtion doesn't collapse into a measurable event. It in fact goes both ways, and each way leads to a distinct new universe. So there isn't any single universe defined by the superposition of wave functions, but a quadratically expanding space of distinct universes, each one with its own definite history.

I think Tony and Luke are both right.

The many worlds interpretation of quantum mechanics is an interpretation. It's not the only philosophy which is consistent with the formulas, it's just one of several interpretations. So by extension, I think both "each state has multiple futures but only one past" and "each state has multiple futures and multiple pasts" are valid subtypes of the many worlds interpretation. Luke can argue that if you're going to accept multiple worlds anyway, you might as well go all the way. But that's still just one interpretation.

Anyway, the Fermi Paradox might be simply be because there is a big sign somewhere that says "Do not feed the Humans"...

(Quantum Mechanics = the universe being undecisive and going with everything)

Ferrell

Tony:

"We're just talking about two different things."

If we are talking about two different things, then you are not talking about the many worlds interpretation of quantum mechanics. In quantum mechanics, all histories leading to the same physical state ("the present") contribute to determining its amplitude (giving rise to the interference phenomena that can be observed). In the many worlds formalism, the macroscopic wave function of the universe is thus a superposition of all possible past histories. This is basic quantum mechanics.

Luke

Luke:

"In quantum mechanics, all histories leading to the same physical state ("the present") contribute to determining its amplitude (giving rise to the interference phenomena that can be observed). In the many worlds formalism, the macroscopic wave function of the universe is thus a superposition of all possible past histories. This is basic quantum mechanics."

Sorry, Luke, but you have your quantum mechanical wires a bit crossed here. From a Scientific American article about Hugh Everett, the formulator of the many worlds interpretation (emphasis added):

"Everett’s radical new idea was to ask, What if the continuous evolution of a wave function is not interrupted by acts of measurement? What if the Schrödinger equation always applies and applies to everything—objects and observers alike? What if no elements of superpositions are ever banished from reality? What would such a world appear like to us?

Everett saw that under those assumptions, the wave function of an observer would, in effect, bifurcate at each interaction of the observer with a superposed object. The universal wave function would contain branches for every alternative making up the object’s superposition. Each branch has its own copy of the observer, a copy that perceived one of those alternatives as the outcome. According to a fundamental mathematical property of the Schrödinger equation, once formed, the branches do not influence one another. Thus, each branch embarks on a different future, independently of the others."

And:

"Explaining how we would perceive such a universe requires putting an observer into the picture. But the branching process happens regardless of whether a human being is present. In general, at each interaction between physical systems the total wave function of the combined systems would tend to bifurcate in this way. Today’s understanding of how the branches become independent and each turn out looking like the classical reality we are accustomed to is known as decoherence theory. It is an accepted part of standard modern quantum theory, although not everyone agrees with the Everettian interpretation that all the branches represent realities that exist."

There you have the many worlds interpretation:

1. Wave funtions never collapse, they simply bifurcate at every point that they can.

2. Conscious observers are a philosophical abstraction; an "observer" is anything that causes a quantum interaction.

Luke:

"In quantum mechanics, all histories leading to the same physical state ("the present") contribute to determining its amplitude (giving rise to the interference phenomena that can be observed). In the many worlds formalism, the macroscopic wave function of the universe is thus a superposition of all possible past histories. This is basic quantum mechanics."

Sorry, Luke, but you have your quantum mechanical wires a bit crossed here. From a Scientific American article about Hugh Everett, the formulator of the many worlds interpretation (emphasis added):

"Everett’s radical new idea was to ask, What if the continuous evolution of a wave function is not interrupted by acts of measurement? What if the Schrödinger equation always applies and applies to everything—objects and observers alike? What if no elements of superpositions are ever banished from reality? What would such a world appear like to us?

Everett saw that under those assumptions, the wave function of an observer would, in effect, bifurcate at each interaction of the observer with a superposed object. The universal wave function would contain branches for every alternative making up the object’s superposition. Each branch has its own copy of the observer, a copy that perceived one of those alternatives as the outcome. According to a fundamental mathematical property of the Schrödinger equation, once formed, the branches do not influence one another. Thus, each branch embarks on a different future, independently of the others."

And:

"Explaining how we would perceive such a universe requires putting an observer into the picture. But the branching process happens regardless of whether a human being is present. In general, at each interaction between physical systems the total wave function of the combined systems would tend to bifurcate in this way. Today’s understanding of how the branches become independent and each turn out looking like the classical reality we are accustomed to is known as decoherence theory. It is an accepted part of standard modern quantum theory, although not everyone agrees with the Everettian interpretation that all the branches represent realities that exist."

There you have the many worlds interpretation:

1. Wave funtions never collapse, they simply bifurcate at every point that they can.

2. Conscious observers are a philosophical abstraction; an "observer" is anything that causes a quantum interaction.

Luke:

"In quantum mechanics, all histories leading to the same physical state ("the present") contribute to determining its amplitude (giving rise to the interference phenomena that can be observed). In the many worlds formalism, the macroscopic wave function of the universe is thus a superposition of all possible past histories. This is basic quantum mechanics."

Sorry, Luke, but you have your quantum mechanical wires a bit crossed here. From a Scientific American article about Hugh Everett (http://www.scientificamerican.com/article.cfm?id=hugh-everett-biography), the formulator of the many worlds interpretation (emphasis added):

"Everett’s radical new idea was to ask, What if the continuous evolution of a wave function is not interrupted by acts of measurement? What if the Schrödinger equation always applies and applies to everything—objects and observers alike? What if no elements of superpositions are ever banished from reality? What would such a world appear like to us?

Everett saw that under those assumptions, the wave function of an observer would, in effect, bifurcate at each interaction of the observer with a superposed object. The universal wave function would contain branches for every alternative making up the object’s superposition. Each branch has its own copy of the observer, a copy that perceived one of those alternatives as the outcome. According to a fundamental mathematical property of the Schrödinger equation, once formed, the branches do not influence one another. Thus, each branch embarks on a different future, independently of the others."

And:

"Explaining how we would perceive such a universe requires putting an observer into the picture. But the branching process happens regardless of whether a human being is present. In general, at each interaction between physical systems the total wave function of the combined systems would tend to bifurcate in this way. Today’s understanding of how the branches become independent and each turn out looking like the classical reality we are accustomed to is known as decoherence theory. It is an accepted part of standard modern quantum theory, although not everyone agrees with the Everettian interpretation that all the branches represent realities that exist."

There you have the many worlds interpretation:

1. Wave funtions never collapse, they simply bifurcate at every point that they can.

2. Conscious observers are a philosophical abstraction; an "observer" is anything that causes a quantum interaction.

Tony:

While the quotes you list from Scientific American are a reasonable layman's description of one of the results of the many worlds interpretation, to really understand the dynamics of what is going on you need to use actual, you know, quantum mechanics and not a description from a magazine devoted to popularizing science to a lay audience.

Do you actually know quantum mechanics? Have you spend years in graduate school pursuing a physics PhD, busting your brain on coursework and then theoretical applications to research problems? Do you then apply quantum mechanics to your day to day work? I have, and I do. And thus I can say with certainty that you are wrong.

Here is how it works. A photon is sent through a pair of slits onto a screen in the classic double slit experiment. The photon hits a certain position on the screen. You can say that this is a superposition of the states |photon goes through left slit> and |photon goes through right slit>. In the many worlds interpretation there is no collapse, so the state of the universe is (A|photon goes through left slit> + B|photon goes through right slit>)|universe where experimenter observes photon at position X> where A and B are probability amplitudes such that A^2+B^2 = 1. There, the universe is now a superposition of the possible past histories of the photon. Extrapolate back and generalize, and you find that the current state is a superposition of all possible past histories leading to the same physical state.

Luke:

"Do you actually know quantum mechanics? Have you spend years in graduate school pursuing a physics PhD, busting your brain on coursework and then theoretical applications to research problems? Do you then apply quantum mechanics to your day to day work? I have, and I do. And thus I can say with certainty that you are wrong."

Please don't get pissy, Luke. I'm sure you know way more than I do about quantum mechanics, and you're pretty obviously an adherent of the Copenhagen interpretation. But you're also pretty clearly unskilled in visualizing evolving systems and describing them formally. (And that's fine, physicists are taught to think symbolically, not in terms of information theory.) Which leads us to:

"Here is how it works. A photon is sent through a pair of slits onto a screen in the classic double slit experiment. The photon hits a certain position on the screen. You can say that this is a superposition of the states |photon goes through left slit> and |photon goes through right slit>. In the many worlds interpretation there is no collapse, so the state of the universe is (A|photon goes through left slit> + B|photon goes through right slit>)|universe where experimenter observes photon at position X> where A and B are probability amplitudes such that A^2+B^2 = 1. There, the universe is now a superposition of the possible past histories of the photon. Extrapolate back and generalize, and you find that the current state is a superposition of all possible past histories leading to the same physical state."

Your problem is that you're defining "history" as something that happens in the past of an event. You are further defining an event as the outcome of all possible histories. That's fine, as a mathematical formalism. It's even fine as an interpretation of reality, if you accept the Copenhagen interpretation.

But...in the many worlds interpretation, the universe is a constantly evolving system in which all histories are equally real and equally valid. Each "world" is defined by its discrete history. Histories can lead to mathematically identical states, but that doesn't mean they lead to the same state. Each history that is in state A at time T is a discrete entity.

To illustrate, imagine we have a binary tree. The tree has two rules:

1. The left descendant of node n has a value of n + 1, and

2. The right descendant has a value of n + 0.

Let the root node, designated node (0,0), have a value = 0. Let's project the evolution of the tree out three levels:

Level 1:

(1,0) = 1

(1,1) = 0

Level 2:

(2,0) = 2

(2,1) = 1

(2,2) = 1

(2,3) = 0

Level 3:

(3,0) = 3

(3,1) = 2

(3,2) = 2

(3,3) = 1

(3,4) = 2

(3,5) = 1

(3,6) = 1

(3,7) = 0

Now, this is obviously a very elementary example, but it illustrates the point. Three possible histories lead to the value 2 at Level 3:

+1, +1, +0

+1, +0, +1

+0, +1, +1

Each history leads to the same state at the same time, but each instance of that state is discrete. Many worlds is just so. As the universe evolves, it takes on every possible state. each evolutionary path from time = 0 is a separate, discrete world, regardless of how many of these worlds may be in the same state at the same time.

Tony:

you're pretty obviously an adherent of the Copenhagen interpretation.

No, I am not. The Copenhagen interpretation is an inelegant kludge which (to me) is self evidently incomplete. Either the many worlds interpretation or some non-local hidden variable interpretation is a possibility for a true theory of how things work (or possibly some other interpretation we haven't thought of yet). The Copenhagen interpretation can be used to get correct results when you have an obvious quantum-classical threshold where the quantum state decoheres, but this threshold is ill-defined in general.

Your problem is that you're defining "history" as something that happens in the past of an event. You are further defining an event as the outcome of all possible histories. That's fine, as a mathematical formalism. It's even fine as an interpretation of reality, if you accept the Copenhagen interpretation.

It has nothing to do with the Copenhagen interpretation. It is a necessary feature of all quantum theories which leads to the interference of paths or states that is fundamental to observed features of the universe that we classify as quantum.

Histories can lead to mathematically identical states, but that doesn't mean they lead to the same state.

They must lead to the same state, or you no longer have quantum mechanics. Instead, you end up losing the interference between paths that is experimentally observed. For example, the double slit experiment would not produce an interference pattern in this situation.

Each history leads to the same state at the same time, but each instance of that state is discrete.

It is not, however, a quantum model and it tosses out the necessary features of a quantum description (the amplitude and phase of each state, and how they interfere).

So...the universe starts in the big bang, has an explosion of innumerable and multiplying world-lines that eventually collapses into the end of the universe...or, so according to Piers Anthony.

Anyway, Quantum mechanics are wonderful for discribing electronics, optics, probability, and particle physics at the subatomic level, among other things; but as far as the beer-and-TV crowd goes, it just makes peoples' heads hurt, no matter how much it really does matter to them and their lives.

Ferrell

Re: Luke

There's state, and then there's identity. Going back to my previous example, if I present you with a state value of "2" on the third iteration, you tell me that that's only one real universe in which that state exists, and that it's the result of the superposition of the three possible histories that can lead to that state. But I, relying on the many worlds interpretation, say no, there are three histories that lead to that state, each one is real, and each one has a distinct identity, defined by the path taken to reach it. You're looking at the world as state, with a mathematical tip of the hat to history. I'm looking at the world as identity, defined by history.

I'm agnostic as to which view is correct, BTW. I'm just trying to adequately illustrate the information content of the many worlds interpretation.

Ferrell:

"So...the universe starts in the big bang, has an explosion of innumerable and multiplying world-lines that eventually collapses into the end of the universe..."

If it collapses, one interpretation is that a single history is selected, and all of the other histories become irrelevant, though they were all real while the universe was running. The "friends of Wigner" in Baxter's Xeelee Sequence, for example, relied on an Ultimate Observer to collapse the universal wave function, and wanted to influence that observer to pick a history favorable to humanity.

Or the universe never ends, it just keeps on going. In which case every possible history occurs, and myriad instances of every possible state exist, each instance within its own history. Of course, in this case time is an illusion of position along the vector of a given history. In reality, the time dimension just defines the axis along which historical vectors extend.

Oh, my!

Tim wrote:

"Either way, it makes it really hard to write any kind of plausible interstellar hard SF"

Well it just means that most of the action will take place in a local solar system...I would think we develop "sleeper ships", ships that might take a relatively long time to get 4 light-years (say it takes them 40 years one way), but the crew doesn't experience it (nor do they age during the trip) because they are asleep/frozen.

If we never figure out a way to freeze/sleep people, then I guess generation ships are the only other option... :(

But I think sleeper ship is a far better option. :)

...and I still say the past no longer exists. That is independent of people disagreeing on when an event occurred. Let's say there is a supernova. Space Station 1 says it happened a year ago for them. Space Station 2, much farther away, says it happened 20 years ago (for them). Both parties actually agree on when it happened, it just took the light longer to reach Space Station 2.

Regardless, I would say that there is no way to go back a year in the past and observe the supernova from close up. For that to be possible assumes that the entire universe is being stored somewhere, every given second, so that men may go back to it. I see no reason to assume this is the case, and no evidence that it is the case.

Perhaps someone has some evidence of that? :-O

The past is inaccessible, it no longer exists. We can go forward in "time", that's all. In fact, I would argue that "time" does not exist, although "duration" does.

Well that's my humble opinion, as a layman, anyway. I've heard speculation that Theories of Everything would eliminate time.

Observe:

http://discovermagazine.com/2007/jun/in-no-time

Re: Luke

I understand your desire to hold on to the "state is reality" POV. And I am quite familiar with the double slit experiment, going at least as far back as college physics (maybe even high school physics, but it's been 30 years).

But many worlds is a "history is reality" interpretation -- otherwise it is meaningless. Each world is a different history. I understand you are having trouble visualizing this. Since we're passing out reading assignments, I strenuously suggest you polish up on the properties of tree-shaped data structures, which can be used to illustrate evolving systems, and are often used in practice to record state in such systems. Then maybe you can get back to us with a less intransigent attitude.

Tony:

There's state, and then there's identity. Going back to my previous example, if I present you with a state value of "2" on the third iteration, you tell me that that's only one real universe in which that state exists, and that it's the result of the superposition of the three possible histories that can lead to that state. But I, relying on the many worlds interpretation, say no, there are three histories that lead to that state, each one is real, and each one has a distinct identity, defined by the path taken to reach it. You're looking at the world as state, with a mathematical tip of the hat to history. I'm looking at the world as identity, defined by history.

The problem with saying that those three histories are distinct is that those histories can interfere and interact with each other. For example, if you get complete destructive interference between the histories, the probability of getting a value of "2" will be zero, even though the probability of getting a a value of "2" if only one such history existed would be non-zero. All quantum systems involve interactions between indistinguishable states in this manner, and thus the state with multiple possible histories ("2" in this case) has no distinct identity since it will always be a superposition of interacting and interfering histories. If it does not behave like this, it does not reproduce observed aspects of quantum systems and thus cannot be an interpretation of quantum mechanics.

I'm agnostic as to which view is correct, BTW. I'm just trying to adequately illustrate the information content of the many worlds interpretation.

But it doesn't illustrate the information content of the many worlds interpretation. In a quantum system with multiple possible paths, there is necessarily no information on which path was taken. If the paths do have distinguishable information content you don't end up in the same quantum state. Again, read up on the double slit experiment for some of the counter-intuitive aspects of this.

Re: Luke

I suspect that our disagreement has many similarities with Everett's and Bohr's. Not that I'm seeting either of us up to be as intelligent and insightful as them -- it's just that it seems to be along the same lines. But, whatever...

(SA Phil)

On the Fermi paradox, FTL travel, and the future of human's interstellar journeys.

------

You dont need FTL travel, immortal humans, time travel, etc - to have interstellar travel.

You just need them because without some sort of "FTL" it makes Interstellar Sci Fi stories different. (No Space Opera)

Thus the most obvous reason for the Fermi paradox is probably also related to our understanding that FTL travel is likely impossible. In that - STL is the way to go.

=======

On Time Travel --

If time only exists because the Universe exists, time travel means extra-universe travel. Which really seems to be a stretch.

My "aliens exist" answer to Fermi had two parts. First, we're not listening to whatever is used for interstellar communication. Be like indians looking to ambush a courier without realizing the message is traveling across those strange trees the white man planted. Also, nothing the tech races do will be visible across interstellar distances. The other answer is that races tha could come here and do come here are observers and so deliberately avoid exposing themselves to us. Don't mess with the nature preserve.

Then there are the other answers ranging from no live aliens existing in our time and space or no aliens ever.

I think there are just as many good guesses for them being out there an us not seeing them as there are for them never being there.

Jollyreaper:

"First, we're not listening to whatever is used for interstellar communication."

But this also means that the aliens are not interested in actively contacting primitives, since if they were it should be well within their technological capability to send messages with means already obsolete for other purposes.

Given how much we seem to want to meet aliens, probably the most likely reason for a civilization to not be interested in meeting others is that it's an alien civilization which has already made contact with several other species, and so the novelty has worn off. If this is how people (human and otherwise) think, then the timespan in which any given civilization is interested in meeting other species is fairly short, so it's realistic that we would have simply missed them.

WRT Fermi Paradox:

I think any answer consistent with the Copernical prinicple is possible. IOW, any answer that doesn't rely on a special status for humanity is plausible.

Ah, the Copernican principle, that philosophical position that lashes out at the idea that something can be too rare or too common. Only the average is acceptable!

Well guess what, some things are rare. And from what we're learning about other stars and exoplanets, we are far from typical here on the Blue Planet. Conditions that would support complex life like us animals, seem to be uncommon in the Milky Way. We see planets with eccentric orbits, water a thousand kilometers deep, wacky elemental makeup, and other instabilities that would make the alien equivalent of multi-celled eukaryotes unlikely to survive. Not to mention that our Sun seems unusually stable WRT flares and variability and Galactic orbit.

So we could very well be at the far end of the probability curve. Or, I'm wrong and intelligent life is common as dirt, they just aren't coming *here*. Maybe humanity smells bad?

Either way, we just can't know with a sample size of one. Until and unless we have First Contact, it's all a guessing game.

Post a Comment