Liberalism in SPAAACE !!!

Click to the original at xkcd to view the mouseover. Thanks to Winch of Atomic Rockets for the tipoff; he is not to blame for my (somewhat belated!) use of it.

This post is, obviously, political. You have been warned. But the political content is not gratuitous. There are plenty of places online where people whom I generally agree with bash on people I generally don't. (See his blogroll, which is actually fairly eclectic.) That is not my objective here. The remarks that follow are specific to the themes of Rocketpunk Manifesto.

I should also note, for a rather international readership, that I am using 'liberalism' in its 'Murrican sense of center-left, not the much more inclusive sense it has in political philosophy (let alone the center-right connotation that it has in some countries). And the entire post is parochial to the extent that it deals specifically with 'Murrican spaceflight. But only three countries have launched people into space; only two on a substantial scale, and I am conversant with the political culture of one of those.

The leading frustration in space geekdom is that while we have accomplished quite a lot in space, we have not gotten as far in space as we hoped, or people 40 years ago took for granted. 2001: A Space Odyssey remains the benchmark of our imagined space present - an alternate world of regular scheduled spaceflights, Moon bases, and human missions to Jupiter. It is the classic rocketpunk vision, with surprisingly little Zeerust.

It did not happen that way, and the basic reason is pretty damn simple: NASA's budget was cut. Reductions from the Apollo era peak were pretty much a given: Apollo was a rush effort to overtake and beat the Russians. That is why, for example, 'Moon Direct' was chosen over the traditional rocketpunk architecture of a shuttle and station first, then moonships.

The amount of cutting, however, was dramatic. NASA's budget peaked in 1965 at $33.5 billion (in equivalent 2007 dollars). By 1969, with Apollo up and running, the budget was down to $21.4 billion. By $1975 it was down to $11.1 billion, and stayed below $12 billion per year until 1983. After that, as the Shuttle entered service, the NASA budget rose modestly, and from 1987 through 2008 (the last year reported), it has ranged between about $15 and $20 billion, averaging $16.4 billion.

The NASA budget dark ages of the 1970s and early 80s were not without consequences, since this was the era when the Shuttle was developed. Richard Nixon reportedly regarded the space program as a 'Democratic boondoggle.' The expression is noteworthy, but his deeds mattered more than his words. He did not cancel the Shuttle program, but he forced a reluctant US Air Force to fund part of its development - in turn for which the Shuttle had to be designed for much larger payloads than originally intended.

What in earlier design iterations had been a sort of space minivan became the familiar space truck - and the combination of a larger payload and smaller development budget forced a fundamental design compromise. What had been intended as a fully reusable liquid fuel TSTO became only partly reusable, and dependent on solid fueled boosters.

We do not know how the Shuttle would have performed if built as originally conceived. There is a serious argument - I have at times endorsed it - that robust reusable orbiters are simply beyond our techlevel: Getting to orbit at all requires an extreme design, and returning in one piece (or even two pieces, for a TSTO) makes for an even more extreme design. You end up not with a truck or minivan, but the equivalent of a racing car that must be torn down and rebuilt before it returns to the track.

On the other hand, the experience of the Shuttle, and its various canceled would-be successors, may simply prove that you get what you pay for, and a severely compromised design is liable to deliver compromised performance.

The Shuttle, in fact, has performed remarkably well given its conceptual shortcomings - a heavy lifter, designed for an entirely new operational realm, but with no development prototype fully tested in advance of the operational vehicles. Its two catastrophic losses were both due primarily to operational failures, not its design shortcomings. Perhaps even more to the point, the design flaws implicated in both losses - the combination of SRBs and external tank for Challenger, and the external tank insulation for Columbia, - were both consequences of the Nixon-era design compromises, not part of the original TSTO conception.

What, you may fairly ask at this point, do particular decisions of a single president 40 years ago have to do with broader political philosophy? The significance is that Nixon's time in office is when the momentum of US political culture shifted against 'big government' and public sector initiatives, of which the space program was the iconic representative.

The downgrading of the Shuttle program thus turned out to be part of a larger political shift, which has affected American space activity ever since. NASA had, and retains, a sufficient base of public and interest-group support that, like Amtrak, it could never be eliminated outright, but it has been kept on a sort of starvation diet, the root cause of many of its failings. If you provide just enough funding to keep a program from dying outright, you keep it alive but ensure that it will be suboptimal.

At the same time an enormous amount of wishful thinking - but not so much actual money - has been invested in the idea that somehow the private marketplace would come to the rescue. But no one has yet managed to come up with the McGuffinite that would tempt big capital to write big checks.

Yes, we now have SpaceX, and may soon have Virgin Galactic, and more power to them both. But let us put them both in perspective. SpaceX aims to tweak and streamline some operational processes within the existing state of the art. It is not remotely an orbit lift game changer. And Virgin Galactic is all about selling the sizzle, not the steak. The sizzle is pretty cool - if I had $200 K to burn, I'd happily buy a ticket for five minutes at the inner edge of space. But the kinetic energy involved is only a few percent of that needed to reach orbit, and orbit is the starting point for space travel in the sense discussed on this blog.

It is always possible that this might change tomorrow - that some McGuffinite will turn up (or at least be strongly enough believed in) that the capital markets will pony up the trillion dollars or thereabouts down payment on the human Solar System. But the smart money has never yet bet that way.

The stall-out of space travel coincides both in time and functionally with the rise to predominance of libertarian economic attitudes. The irony is striking, because 'Murrican space-mindedness has deep and long connections with libertarianism, going back at least to Robert Heinlein.

It has been noted here and elsewhere that the ethos of rugged individualism associated with libertarianism is (absent some major magitech) a poor fit for the requirements of living in space. It also turns out to be a poor fit for getting there.

No, I don't expect anyone to leap up onto the stage, throw away their crutches, and proclaim that they have been healed! People adopt political philosophies for varied and complex reasons, and for that matter everything is not about space. I am merely noting that if, as a matter of principle, you rely on the private marketplace for nearly everything, don't hold your breath waiting for it to provide extensive space travel.

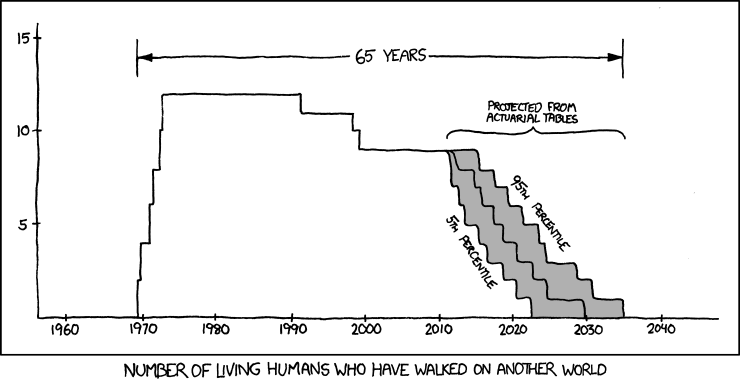

Standard provisos apply. The discussion above is focused on human space travel, but there is an argument to be made - I have sometimes made it - that going in person is nearly irrelevant to, or even a distraction from exploring space. In spite of xkcd, our robotic probes have opened up the Solar System to an extent no one in the rocketpunk era ever imagined.

Other provisos. It is certainly no automatic given that, had the liberal project continued through the last 40 years, it would have necessarily included a vigorous space program. The Space Race might have ended anyway once a touchdown was scored. And a significant segment of the 'Murrican liberal coalition has - at least since the 1960s - shown a marked, Thoreau-esque distaste for big noisy things that go fast.

It is also arguable that other strands of the 'Murrican right are not necessarily so unfriendly toward large public initiatives. 'National greatness conservatism,' of the sort sometimes championed by neoconservatives at the Weekly Standard, might well be open to a major space effort. Indeed, rhetoric along those lines accompanied the GW Bush administration's talk of going to Mars, which produced 'Constellation.' The rhetoric, alas, was not accompanied by funding, and ended up leaving NASA in a very awkward spot.

Once again, you get what you pay for. And to the degree that we wish society to consider space travel - human or robotic - profoundly important, I will argue that we must at least consider whether society, through a public initiative, needs to step up and pay for it.

It is tempting at this point to say "Okay - let's rrrrumble!" But as always in these comment threads, light is more useful than heat.

So I will merely say: Discuss.

(The Saturn V launch image is from NASA.)

117 comments:

The Space race was fueled by patriotism and a certain amount of sabre rattling (early Soviet boosters really were ICBM's, and Project Apollo had an undertone of "See what we are really capable of? Don't push it, bub."), so I am a bit uncertain as to how Liberal political philosophy really would have impacted it. Americans were hurt by the challenge and seeming success of the USSR in the space arena, and I think that even a Republican administration under Nixon (had he won against Kennedy) would still have coughed up the money.

The space race wound down because there was no more political McGuffinite, just enough political pork to keep a smaller space program going to satisfy various congressional clients.

I have to quibble (What's new, right?) about the success of the Shuttle progam. It was a technical success within the context of achieving certain performance goals. It was a political success within the context of surviving as a program, and meeting certain "national greatness" goals. But it was manifestly not a success WRT delivering on promises to the investors (in this case, taxpayers). Nor was it a success within the context of bang for the buck -- putting 120 tons in orbit, then bringing 100 of those tons back, is just not good business.

Let's leave politics entirely aside. Imagine what could have been done, on essentially the same budget, with repurposed and ultimately evolved Saturn series launch vehicles. Forget Mars. Forget even the Moon. How big a space station? How many space stations? How many Hubbles or equivalents?

Going back to politics, Shuttle, in any form, was the original political sin. Nixon didn't want to do the cost and risks of Mars, but he didn't want to cede progress to the Soviets. Shuttle was progress (for certain values of "progress"). It was a way to do something the Soviets weren't doing, without going interplanetary.

Now, it is certain that many people in NASA believed in reusability, as did many in the supporting industrial base. But many didn't, and could show you the math of why it wouldn't work, using chemical rocket technology. So the Shuttle wasn't just handicapped by politics, it was handicapped by reality. Combine the politics of the Shuttle's existence with the reality of its existence, and we can point directly to the Shuttle, and nothing else, for why we haven't progressed further, in terms of tonnage in orbit and numbers of people to experience spaceflight.

Severe tangent and not really tied to the subject of the post but still tickles my mind > I wonder what this would tell us about how governmental structures would develop in space (when it happens) and how -they- would react to further expansion.

Well, if you want to see funding increase for space flight of both sorts, Manned and Robotic, all we need is a Big Hunk'n Rock(1) to smack the Earth and get all the groundhogs to perk up and take notice that there's something up there that can hurt them.

The average person won't pay for space flight unless they see a need. If a BHR were to detonate/impact near a major city that would get them to open up there wallets.

The other reason for them to spend money is if there's something that can be Found Only In Space, and it's worth the trouble to get, then you'd see investment to exploit that FOIS. So far, I don't know what that is. Planets are nice, especially those with tectonic processes, because they can concentrate minerals through geological processes, while asteroids are generally uniform in their composition. Thus forcing you to smelt them and refine them to an extent that we don't have to on the Earth.

(1) For values of BHR that do sufficient damage but not enough to End The World As We Know It. Something Tunguska range would be nice. :(

kedamono@mac.com:

"(1) For values of BHR that do sufficient damage but not enough to End The World As We Know It. Something Tunguska range would be nice. :("

Tunguska happened. Shoemaker-Levy 9 happened. The response was mildly increased funding for asteroid detection. Even if a BFR hit the Earth, somebody would (quite correctly) point out that it was a rare event, with a vanishingly small chance of being repeated in actuarily significant time, and that the only expenditure really justified would be better surveillance, plus a low intensity development program for deflection technology.

Traditionally, when a new technology or new mode of transportation was new, governments would sponser races to spur developement...the race to orbit that Burt Rutan won was a start, but a regular race (with a big purse and/or presigious trophy).

It would seem that rocket races are long overdue; not just the rocket-powered planes that seemed to fade away, but real rockets and a real set of races; one to orbit and back, one in orbit, one around the moon and back. Years ago (ok, decades) I read a story about a rocket race around the solar system; it was the most popular and pristigious event of its day. Maybe we need something like that; let the sport and entertainment bring in the bucks to fund the real development in the background.

Ferrell

"...the race to orbit that Burt Rutan won was a start, but a regular race (with a big purse and/or presigious trophy)."

There should have been "is what is really needed" at the end. Sorry.

Ferrell

I sometimes wish really out-there free-marketers would bother to draw some analogies from those fields of scientific evidence that end up making so many technogoodies in those markets they hold so dear. They might notice that all these systems that are rough analogues of market behavior, like biological evolution, for instance, are all made of swarms of short-sighted agents that are really good at maximizing local extrema, but really terrible at climbing over the adjacent hill (or valley, depending on the view) to reach a global one. A circulatory system seems marvelously designed, each vessel represent an optimum of physical factors governing its geometry- until you find one that loops six inches out of the way because the "blind watchmaker" couldn't feel his way to the other side of a structure in the ten million generations since that layout made sense- in a fish- a task that a human child could do.

On one hand, we have those who have correctly noted that at prices that have held for some decades, it wouldn't make monetary sense to ship back free-flying bales of cocaine from LEO, and that the solar system consists rather uniformly of places that try to kill human beings, and that the billion dollars spent on a rocket can pay for a lot of (hopefully) immunized children, (unfortunately routinely) ordnance either mouldering or used to rearrange desert villages, or (in populist rhetoric) left in your pocket to go see Thor in 3D, and thus we sit on our warm and cozy blue dot. On the other hand, you have the advocates, from far left to right to slantways, who have also correctly noted that whatever it is you want- metals not dug up from under old growth forests, enough solar and nuclear energy to run the heat all winter, space to stretch your legs, rocks to turn over and sample, adventure vacations to take, spots to reboot and back up civilization, destinies to manifest- there is essentially infinitely more of all the above in places that are not at the bottom of this particular gravity well. In both zones, we have conditions where the rough-and-tumble efficiency-maximizing magic of free markets out to work just fine- but between them is what looks suspiciously like a massive activation energy, on the order of a couple working lifetimes and the spare change in every couch on the planet into perpetuity- and "I'm Going to Tax You Your Whole Life For Shit You Won't Get to Use" has never been a terribly effective campaign slogan, as productive as such candor might be.

Rick: "It has been noted here and elsewhere that the ethos of rugged individualism associated with libertarianism is (absent some major magitech) a poor fit for the requirements of living in space. It also turns out to be a poor fit for getting there."

Probably true, I suspect in the near future the best bet would be a government-funded space elevator or similar as the foundation for the private exploitation of the solar system (assuming it really does slash costs enough).

Yes, there's lots of useful stuff in space for people living in space -- but not for anybody else. If you had a large, viable space civilization, why would it bother trading with the Earth for anything? It wouldn't. To be big ans successful enough to have surplus to sell to groundhogs, what do you need worth the expense of shipping it up out of a gravity well?

So there probably won't be any McGuffinite shipments back to the Earth, even if McGuffinite existed. The spacers would tell the Earth, "We've got plenty of uses for this stuff up here. NOw go away or we'll start dropping rocks on you."

The Space Race was definitely directed by economics from beginning to end - I recall reading that the main reason the US got to the moon first is because the USSR started cutting its funding earlier, allowing the US to overtake them even while the USSR had achieved the first few space milestones.

Once hostilities winded down - as famously symbolized by the Apollo-Soyuz project - it was inevitable that funding would be cut.

Rick:

"going in person is nearly irrelevant to, or even a distraction from exploring space."

There is some scientific data that necessarily require going in person to obtain - namely, on the effects of low-gravity (not zero, but Lunar, Martian, etc.) on the human body.

Of course, if you have no reason to go into space, then that raises the rather circular question of why you even want that data...

"In spite of xkcd, our robotic probes have opened up the Solar System to an extent no one in the rocketpunk era ever imagined."

True - but at the same time, it's kind of depressing whenever I read something about "Cool - this really awesome probe was just launched successfully!" (which is a cause of celebration, since launch time is the most stressful time on your equipment), and then realize that it'll be years or decades before it arrives and we get any results.

And probe data on my current favorite body - Titan - is remarkably scant. The Huygens probe lasted for an hour and a half, and they didn't even include a color camera. The atmospheric haze limits what can be seen from orbit. Last I checked, we didn't even have a detailed full-globe map, let alone a visible-light true color one!

Or look at the Spirit rover. Something that a human could easily solve simply by yanking it out becomes a mission-ending problem, because there are no humans on site.

Probe data is far better than nothing, but far worse than what a team of humans with a well-stocked lab could do.

But maybe, with good automation, we could at some point in the future send a well-stocked lab that can run itself. That still requires transporting much larger masses than we already have.

kedamono@mac.com:

"Well, if you want to see funding increase for space flight of both sorts, Manned and Robotic, all we need is a Big Hunk'n Rock(1) to smack the Earth and get all the groundhogs to perk up and take notice that there's something up there that can hurt them."

Detection and deflection of near-Earth asteroids requires entirely different platforms than exploration or colonization of remote bodies. Spending resources on an asteroid deflection program would take resources away from other space programs.

Ferrell:

"It would seem that rocket races are long overdue;"

Unfortunately, a race requires multiple people interested in and able to produce appropiate vehicles. There currently just aren't enough spacegoing companies, and the ones that exist have better things to do with their time and money, to fill one race.

Z:

"enough solar and nuclear energy to run the heat all winter"

Life support and fast space travel both need vast amounts of energy. (There's a lot of winter heating needed on Mars!) And we seem to have enough uranium here on Earth for the time being - now if only we could get people to stop panicking every time you say the word "nuclear"...

"space to stretch your legs"

Of which there is more of in even a cheap first-world apartment on Earth than there is in a mass-constrained closed life support habitat.

"rocks to turn over and sample, adventure vacations to take"

Okay, you got me there. Space does offer an advantage on those.

Titan's rocks being made of oxidane really amuses me. I'd love to see one of those close up.

There is also a cultural aspect to think about. Europeans spent lots of time and energy traveling around the world, killing, enslaving and exploiting everything they could get their hands on from the time it was possible (Alexander the Great comes to mind, but perhaps his illustrious and somewhat mythical predecessor Agamemnon's visit to Windy Ilium might serve as a good starting point).

The British modified the pattern by emphasising commerce over mere conquest and exploitation, while Americans have turned out to be pretty big on the commercial empire thing.

Since former drivers like the glory of God, subduing enemies, converting pagans/heathens/apostates, finding new estate for the second and third sons, finding new agricultural land for the peasants don't obtain anymore and commercial drivers are really not strong enough (a reasonably doable program called AsterAnts offers solar sails to suspend satellites in non standard positions to increase the number of geostationary "slots" available. The estimated value of these new slots is $2 billion; which is pocket change to aerospace companies), there is no real reason to go.

If some sort of magitech brings the costs of launch down to (say) the price of an airline flight or even steamship travel in the early part of the last century, then lots of people will probably go, impelled by curiosity or the desire to take a chance where the risk/reward ratio is somewhat realistic. Space hardware does not have to be very expensive (Bigelow inflatable modules are conceptually very rugged balloons, and lots of things can be done with mirrors), the problem is getting it out there in the first place...

I have to disagree: the reason why vision form 2001 Space Odyssey didn't come true wasn't because NASA's budget was cut. It didn't' come true becuase it was unrealistic. And no amount of money would change that. Sure, we would have landed on Mars at some point in 80's as von Braun planned (or at worst at the beginning of 90's). We would have some outposts on Moon made from post-Apollo modules, but that's it. There wouldn't be flying space cities, or Moon cities for that matter because they were-and still are- outside our technological reach. But most importanly all those space acitvities are too resource consuming and pointless from economy point of view. To put it bluntly: we have no interest being there. And honestly-cutting budget isn't the problem. NASA is. The only way to have rocketpunkt is to shift from spending-space to investing-space model, becuase only then someone could realistically explain why so much stuff flies in space. So no "liberals" but "libertarians" in space. NASA since 20 years had technology to change spaceflight and space exploration. But it was unable to make any use of it. Bigelow Aerospace had to buy plannes for Transhab and make use of them. Why? Because with all those billions NASA has political goals (not tehcnological, scientific etc) and is put under bureaucratic pressure. So, utlimately, it is doing only pointless things in msot ridicolous manner possible. Because its goals aren't rational in common sesne of that word. Because if NASA was rational and indpeendent, it would never-with such shrinked budget-fly this needles monstrosity called Space Shuttle, but would continue post-apollo program, build more Skylabs and fly there atop small rockets in Apollo capsules, and would contiune exploring Moon with use of smaller rockets-launching two or three to get the job done.

I advice anyone, who disagrees to check site astronatuix.com, read material stored there about all realistic rockets, Moon exploration programs etc and assume that US and USSR would engage in space race till 90's, so all those beatifull things would be build and answer the question: has the world changed? And then answer second one: is this scenario realistic?

Setting aside the notion that the U.S. is some sort of free-market, libertarian paradise for a moment, what might NASA accomplish with an annual budget of $100 billion?

Gentlemen;

It would seem that the particular problem is that going into space is hard, expensive, and for populations that are more interested in ‘Murrican Idle, seemingly unimportant. We, the few who understand Space and the frontier it represents, are alone. People no longer dream the big dreams, most likely because they are so involved in just trying to make the here and now work out, that they forget to look up.

I confess that I too have been finding myself looking down more and more, wondering why things just don’t seem to be working. It would appear that the lowest common denominator has taken a hold of our society. What we might be forgetting is that the military industrial complex that facilitated Apollo has been so institutionalized and politicized that it no longer has the aggressive intellectual dynamic of that era. Instead we are dealing with politics and budgets, negotiation and committees, cautious and overwrought specifications, but very little in imagination or engineering. It’s all systems analysis, but no sweat. Metal isn’t being cut, wires aren’t being harnessed, and concrete isn’t being poured.

We have institutionalized our risk aversion. We are afraid someone might die, in a flaming ball of shattered carbon fiber and titanium. Our government, and those corporations who might also be capable of such projects, live in fear of the 24/7/365 news cycle. Paralyzed by our “What if’s?” we find ourselves looking down, turning to our high calorie, sedentary lifestyles, and tuning out the inner voice that has pushed us for the last 10,000 years. There will be no singularity, no space colonies, just slightly better tools, and then finally, an idiocracy.

Oh, and just to clarify (sorry for not including that in previous comment): my point is that there is NO way to have rocketpunk setting with realistic assumptions. Nor private enterprises nor government spending-nothing can change that. Even if that spending is huge and pointless-that is its only goal is to burn money in space. You will get your horse and armor, but there still won't be castle with princess to save or dragon to fight with. So you will end up up there bored to death. A poor scenario for story, don't you think?

But if you still don't care, if you just want ot have horse and armor then you should connect those two types of thinking. Mimic what is happening today with ISS. Join frivolous governemnt spending with elasticity and efficency of private companies. Shuttle is no more, but America is paying Russians for flights and is funding development of private counterparts of Soyuz spacecraft. Thanks to that SpaceX can dream about Mars flights. So the answer lays here: cut NASA's budget or phase Agency out, but force America to stay in space nevertheless (Cold War/continuation of space race for instance). NASA won't be up to the job-always too late, always too expensive so outsoruce that role to private companies. Do the same thing in your setting which is hapenning right now but just 40 years earlier and you will have your horse and armor. Still no princess though...

"It would seem that the particular problem is that going into space is hard, expensive, and for populations that are more interested in ‘Murrican Idle, seemingly unimportant."

The problem is, there's good reason to query that "seemingly".

Absent a spectacular breakthrough in unified field theory, it seems like we've got nowhere to go in space outside our solar system, and now that we've fileld all the GEO slots with commsats and MESSENGER has orbited Mercury, we've pretty much scooped all the plausibly reachable fruit around Sol.

Yes, we could put spam cans in orbit around the rock of our choice. With a huge effort we might be able to make those cans moderately self-resupplying (though we've never yet managed that even here on Earth).

But what could we conceivably put in those cans that makes them worth the cost of launch? And if we could build closed biospheres, why not first deploy them in the deserts and oceans of Earth?

I would argue that it's the uneducated TV-watching public who look at space and see a shiny Star Trek frontier. Those with a bit more knowledge can run the math and wonder what the point of it all is, now that we've got GPS and Hubble.

Building better space telescopes, as a justification for billions in research, feels like upgrading from DVD to Blu-Ray. Yes, you get prettier pictures. But at the end of the day, does adding a few pixels to our skymaps actually make us smarter people?

Or is space just, really, a big-screen entertainment system for scientists with no potential for ever transferring into actual technology?

Particle physics, I can see the point of that. Subatomic events occur on human timescales. Cosmic events, not so much. Even if we learned that our galaxy was going to explode in a million years rather than a billion trillion, it wouldn't help us solve the peak oil problem.

So what's the actual point of space?

Hmmm...scrap the manned portion of NASA's mission and offer a billion dollars to the winner of a biannual rocket race. Have different categories; private, corporate, unlimited; to orbit, in orbit, around the moon, ect. Spend a couple of million dollars in advertising on the race and-vola-you have NASCAR in space! That should drum up support...

Ferrell

Even space races might not be enough to do the trick. There was a proposed solar sail race to the Moon for the 500th anniversary of Columbus voyage to the new world. A Canadian team proposed a ship which resembled a hexagonal Venetian blind, and there were a few other entries, but no one ponied up enough money to actually build any of the entrants, much less launch them into orbit, much less fill the coffers with prize money...

If there was real prize money, then something like Robert Zubrin's "Mars Race" might actually work (a series of prizes with the ultimate goal being a cool $30 billion when your crew gets home from Mars). The money must actually be there in escrow, otherwise potential competitors might not wish to put their money up front to build a spaceship...

Space based solar still might hold the promise of enough cash to lead to further development of launch vehicles, but that's about the only thing that works in the short term.

Long term, as in at least a hundred years away, the greatest resource that we're going to need from space is vacuum.

Vacuum is valuable because it contains nothing valuable. You can do horrendously dangerous things there, stuff that nobody would ever consider doing on Earth, and run only minor risks. I'm thinking along the lines of fairly advanced tech concepts like trying to handle micro black holes, or building general purpose potentially self-replicating nanotech assemblers. It might even be something as simple as new artificial insect species that we don't want to risk releasing into the wild.

Scary ecosystem-destroying tech has its place, and that place is far, far away from Earth.

I think your analysis of the politics is a bit simplistic. Liberals began turning against the space program earlier than you suggest -- Walter Mondale used the Apollo 1 fire as a pretext for hearings, and William Proxmire was attacking NASA (and SETI research) in the 1970s. Neither man was remotely libertarian.

And you had the old-school fellow-traveler left criticizing the whole effort right from the start, because it was competing with the Soviets, and it was "warlike."

Hell, look at how Stanley Kubrick subverted Arthur C. Clarke's vision in 2001 -- where Clarke saw space exploration as liberating and transcendant, Kubrick went out of his way to depict it as tedious and dehumanizing. The "smart set" was turning against space exploration before we even got to the Moon.

No political movement will be much in favor of space exploration, because it has little to do with the things politicians value. Trying to blame one party or the other is dumb. The reason so many of us place our hopes in private space exploration is simply that we know government will never have much interest, and you can't build any kind of long-term presence on the whims of politicians. To be sustainable, it must be profitable. We need to find ways to make it so.

To start, my political views are conservative. I'm not interested in a debate, I'm just getting it out there.

That said, I really don't see a change in political leadership having a big impact on the space program. Presidential support for space has far more to do with the president than the party. I've read that George W. Bush actually cared about the Vision for Space Exploration. It wasn't just political. Obama obviously doesn't care enough to understand a bunch of this stuff, as evidenced by his speech last year.

The biggest difference between Apollo and what has come after it is not liberalism but war. To quote Schlock Mercenary "Governments are only competent at war, and only barely competent at that" and to mangle Clausewitz "Policy is the continuation of war by other means."

Fundamentally, Apollo was a war program. The shuttle wasn't.

Also, they had vastly different engineering tasks. Apollo's mission statement was simple. "Land a man on the moon, and bring him safely back." Everything else was secondary. The shuttle had to be all things to all men. This meant that development costs were far too high, so we got what we have today.

Lastly, the experience of the soviets makes me doubt the basic premise of the post. They had a far greater love for government programs then even American liberals, but they didn't really beat us in space after Apollo. They had Mir, we had the Shuttle. It was basically a tie.

Milo:

I recall reading that the main reason the US got to the moon first is because the USSR started cutting its funding earlier, allowing the US to overtake them even while the USSR had achieved the first few space milestones.

I've never been impressed by those sort of space milestones. Most were matched within months by the US. The one that wasn't (women in space) was irrelevant from an engineering perspective.

Cambias:

"Hell, look at how Stanley Kubrick subverted Arthur C. Clarke's vision in 2001 -- where Clarke saw space exploration as liberating and transcendant, Kubrick went out of his way to depict it as tedious and dehumanizing. The "smart set" was turning against space exploration before we even got to the Moon."

Really? If anything, Kubrick was being a wild optimist. Look at his space shuttle, complete with an airliner-like passenger cabin and sexy stews. Compare his wheel station -- with pay phones that accept debit cards no less -- to the ISS. And the Discovery? A luxury hotel compared to what interplanetary vessels are likely to be like in the next hundred years. Yeah, all the action was happening in slow motion, but that's, well...space travel.

Because we can't find a for-profit motive for space travel, perhaps we should concentrate on building scientific outposts off-world; present them as on-site labratories like what we have in Antarctica. Deemphasize compitition, 'space race', conquest, colonization, and talk up these off-world bases as 'local control and first-stage labratories' to enhance the robotic probes already on-world. That this will take many, many years, and many billions of dollars will undougtedly be used against this approch, should be countered by pointing out that the current approch isn't working at all.

Ferrell

Welcome to a couple of new commenters!

Other than that, I'll simply watch the stew continue to bubble.

To be frank, I don't think a lot of people actually care if space exploration works out or not. I think the presumption of most is that it will proceed at the speed that it can, when it can, but it just isn't part of their personal future, so why GAS?

Those of us who are children of the Space Age can remember a time when space was top-of-mind, with a huge mindshare base. Nowdays it's just another form of high fantasy in entertainment, or something geeks do to bring you HD TV. IOW, it's either simply unreal, or it's boringly mundane.

Looping back to the "how and why", it occurred to me that if Richard M Nixon had beaten Kennedy and was the President who decided to go to the Moon, our contrafactual history would actually have turned out to be more Rocketpunk than we ended up with.

First of all, Nixon would want the program to proceed quickly and cheaply, so rather than entrust NASA with the Moon program, he probably would have turned to the various existing military space programs and (probably) given the USAF the lead.

The Air Force would need to adapt or create stuff that could be launched into orbit on existing boosters like the Titan, so in orbit assembly would be the order of the day. Extending hardware like "Blue Gemini" to carry three crewmen into orbit, hooking up to extended versions of the RM-81 Agena to get around, and the LEM carried up separately to make the lnar package.

If we want to have more fun, we could suggest that programs like the Dyna Soar and MOL would have made it into service. The MOL would serve as a big, comfy RV for traveling to and from the Moon, with the lunar lander and re entry vehicles stowed on external docking collars once everything was assembled. Apollo 8 would have swung past the Moon observing potential landing sites with the high power optical equipment (MOL was actually a manned recon satellite).

This is a pragmatic response to a problem, which "conservative" (Classical Liberals, see Edmund Burke) would probably more likely to consider rather than building totally new institutions and things, which is the sort o response a "Progressive" would be more likely to consider.

Reality is for a project like the Moon shot, a mixture of pragmatism and idealism is needed (even the new Saturn boosters and Apollo spacecraft were simply scaled up, state of the art space hardware that evolved from previous practice). Politics intrudes on various choices (LBJ used the program to spread pork all over to industrialise the South) and the ratio of pragmatic to idealistic, but can only go so far if the project has any chance of success.

I'm sad that Dyna-Soar never seemed to make it. I watched the 1968 movie "Marooned" a few years back in which an Apollo/Skylab-esque mission is saved by both a Soyuz and a Dyna-Soar type Air Force lifting body. Fun times.

I grew up in the 70s with post-Apollo space fever, and although Challenger shook my faith space travel would ever be an "ordinary person" kind of thing, it took me well into the 90s to realise just how once-sided the 60s space propaganda was.

I still think space is cool - skysurvey.org makes me realise again just how much stuff is out there - but I feel really bummed that it's all pretty much lethal or unreachable.

I love the pictures the robots are sending back. Glad I live in an age where I can surf Mars in VR. And if I were in space I'd still be doing most of my exploring via mediated virtual telepresence. But I don't know how to cheer for the Space!Future any more, except as desktop wallpaper for Windows.

It just feels to me like the most plausible midfuture is a small-s singularity on Earth: an energy/climate/resource crunch and period of accelerated social change that I simply can't see beyond. There'll be a society after peak oil, I think - but I don't think it will involve either colonising other planets or uploading consciousness to machines. I don't know what the new horizon is. For the first time I sense a world *without* a frontier, and that scares me.

If anything, I see the Net bringing about an implosion of cultures, a sense of connectedness into a single human identity, with conflict over just what that identity means.

I think we've lived with the consciousness of a New World for so long - five hundred years and change - right alongside the science and tech explosion - that we're not quite mentally equipped to deal with the emerging realisation that there *are* no new worlds left, no space to "get away from everyone", only a single unified web. That's hard. It's like giving up a house for a shared flat.

The Cyberpunks almost had it right, I think, but there's still a wistful dream of the Net as a last unspoiled frontier. I don't think we'll even have that. For the first time we'll have to face up to our neighbours and the smallness of our shared world.

I don't know how I can do that, but I don't see any choice.

We are definitely going to colonize other worlds. The further in the future you look, the greater the probability it has already happened. This does not mean that NASA will do the colonization. I think we should colonize space the way we colonized North America: through private groups. Jamestown was not populated by His Majesty's Navy, but by private citizens. The equivalent of Lewis and Clark, these days, will be robotic probes, but the people who colonize will be civilians.

The “liberal” crusade of the 21st century is halting anthropogenic climatic change. Space technology would be a more effective and controllable way of doing so than experimental chemistry. Orbital solettas could regulate insolation, preventing both hot houses and ice ages.

While we’re up there, we could try out orbital power generation. Maybe we would even need some Island-3 habitats to house the construction crews. Who knows what might develop after that?

Re: Thucydides

Project Mercury was alread well in hand by the 1960 election. Project Gemini was pretty much conducted in the way the Air Force would have, using an ICBM launch vehicle. Past the Titan, the Air Force just didn't have a launch vehicle of its own. And the Titan's 3.6 tons to LEO performance wasn't going to support a Lunar effort.

The Air Force would have had to go to Huntsville to get Saturn rocket technology. And they probably would have waited on at least the S-IB version, with its 21 tons to LEO performance. It should also be noted, however, that the F-1 engine that went in the Saturn V first stage was originally an Air Force project. They abandoned it because they didn't foresee an application (largely due to the unexpectedly small fusion weapon sizes that were achieved in the late 1950s). But given the Moon as an institutional objective? One wonders just how much less grandiose and costly an Air Force program would have ultimately been.

I agree with Cambias. The future of colonization and space travel is with the private sector. Just as most ships on The High Seas are merchant or private vessels, most ships in space would be as well. North America was settled not by His Majesty's Navy, but by private citizens (albeit with His Majesty's Cash and Endorsement). :-)

Once there is a significant private presence in space, we might have a need for a Space Navy. But initially, most of it will be private action, as well it should be.

There is no need to ask military/NASA heroes to risk their lives just to get scientific data, and colonies are not built by military personnel. Hence, the Lewis and Clark missions of space should be done by robots, as they are now, and the colonies that follow should be composed of civilians. :-)

Brian:

"I agree with Cambias. The future of colonization and space travel is with the private sector. Just as most ships on The High Seas are merchant or private vessels, most ships in space would be as well. North America was settled not by His Majesty's Navy, but by private citizens (albeit with His Majesty's Cash and Endorsement). :-)"

The private sector doesn't have any motivation to be involved in space except Earth-centered applications and government contracting. And nobody's going to colonize space just for the heck of it.

"Once there is a significant private presence in space, we might have a need for a Space Navy. But initially, most of it will be private action, as well it should be."

States will protect their own interests wherever they are. That means they will have space forces to the degree they have interests in space. It doesn't take private property that needs protecting.

"There is no need to ask military/NASA heroes to risk their lives just to get scientific data, and colonies are not built by military personnel. Hence, the Lewis and Clark missions of space should be done by robots, as they are now, and the colonies that follow should be composed of civilians. :-)"

Space settlements may be composed of civilians, but they will be government employees for a long time in the future.

WRT the risks humans should or shouldn't take, humans will go where they can do a better job than machines. Nobody's asking any "heroes" to risk their lives, scientists want to go and see these places first hand and do their field work like they do on the Earth.

@Tony:

"Humans will go where they can do a better job than machines."

Which rules out pretty much everything except staying at home doing something artistic. A Robotic camera with some manipulaters can do more than enough. Staying at home and having the results beamed back to analyse is all that's needed.

There are things simply too large in scope for private industry to attempt. Or at least too big for them to fund themselves conventionally.

I'm a fan of the idea of the government providing the funds and industry providing the solutions. However, it doesn't work out that way most times.

The point above about "what are the goals here?" is right on. Constellation was a highly successful program in that it made billions for the contractors. That it was canceled is no problem; they're still getting paid termination fees.

It seems like with most human projects, you need a small team of dedicated people who will live for the project and then you leave them alone to do their thing. And you really need someone with vision to drive the project, no leadership by committee. Of course, a dictatorship is the most efficient form of management but it can also be the quickest way to crash-dive the project into the dirt.

Honestly, I don't have any good answers. Large bureaucracies become self-perpetuating and private industry is just corruption by another name. If we can solve the problem of organizing human society in a way that doesn't inevitably fail, space travel would be just one of a thousand things worked out as a consequence of that. I wouldn't hold my breath though. :(

Geoffrey S H:

"Which rules out pretty much everything except staying at home doing something artistic. A Robotic camera with some manipulaters can do more than enough. Staying at home and having the results beamed back to analyse is all that's needed."

Steve Squyres, the principle investigator on the Mars Exploration Rover program has said more than once that a human on-site could have done more in minutes than the MER rovers did in days. Once again, the scientists only put up with robotic probes because economics keep them from going themselves. If the economics changed even a little bit, scientists would drop proposals for robotic probes and start polishing up their CVs with science crew selection in mind.

tony wrote:

The private sector doesn't have any motivation to be involved in space except Earth-centered applications and government contracting. And nobody's going to colonize space just for the heck of it.

Currently, the private sector is involved in space for tourism.

I think people will in fact colonize space for the heck of it, just as they climb Mt. Everest for the heck of it. If you have a lot of money, and you're into that kind of thing, you do it. Eventually access to space will be cheap enough so people who don't have a lot of money will be able to go, too.

But many will go because they want to form their own governments, live under their own rules. That's one of the reasons people came to North America; they were fleeing the oppression of Puritanism in England.

For example, there might be a space colony devoted to libertarian ideologies, and another devoted to communism (I consider myself moderate liberal, but between two choices, I would live in the libertarian colony, and I would fight for the libertarian side in a war).

Space settlements may be composed of civilians, but they will be government employees for a long time in the future.

Why??? Was Jamestown settled by His Majesty's Navy?? No, they were civilians, that is to say, they did not work for the government. :)

The biggest thing we need to fix is make sure we allow private individuals to own land on bodies in space, that is to say, we need to modify the Outer Space Treaty. It is silly to suggest that someone should not be allowed to own land on Mars. :)

--Brian

Brian:

I think people will in fact colonize space for the heck of it, just as they climb Mt. Everest for the heck of it. If you have a lot of money, and you're into that kind of thing, you do it. Eventually access to space will be cheap enough so people who don't have a lot of money will be able to go, too.

I'm not so sure about this. Access costs will have to fall so much that we're outside of the PMF. The same applies to homesteading or anything of the sort.

The biggest thing we need to fix is make sure we allow private individuals to own land on bodies in space, that is to say, we need to modify the Outer Space Treaty. It is silly to suggest that someone should not be allowed to own land on Mars.

Actually, all the OST forbids is government ownership of celestial bodies. Private and corporate ownership isn't prohibited. The Moon Treaty, on the other hand, does prevent that, but it's not in force.

Re: Bryan

You're reading from a twenty year old playbook that has been shown to be invalid.

Space tourism has put seven billionaires in orbit for an average of twelve day apiece. That's using extremely mature technologies, with no obvious successors waiting to take over and make things cheaper or otherwise more accessible. Heck, it's a more exclusive club than owning your own personal 737. It's likely to remain so for the foreseeable future.

As for people like Rutan and organizations like Virgin Galactic, they're trading on the much more easy to achieve suborbital experience. That's an achievement not even as old as manned spaceflight, and one that was barely news, even shen it was new.

WRT politically motivated space colinization, there are a couple of things standing in the way:

1. Most obviously, we have found out that survival in space cannot be a laissez faire enterprise. It requires discipline and cooperation on the part of all involved. People who want to be free need not apply. Now, that actually applies to the Puritans, who were a pretty repressive bunch, and who needed significant levels of community cooperation to survive their first several years. But there is a second problem:

2. The cost is just insurmountable. It would take space being as cheap as aerial flight (at least) for small communities to use their savings to rent a couple of ships and take off on their own into the wilderness. In fact, it wouldtake a situation pretty analogous to that which existed in 1620, where fisherman had been fishing off the coast of North America for over 100 years, and just going there was a pretty routine, unnewsworthy thing.

(SA Phil)

A conclusion based on some contentions in an earlier blog entry --- the definitions of "rich" and "poor" change with technology and development.

Thus even in today's world of proportional wealth being increasingly concentrated at the top; the "poor" are basically "richer" than in earlier time periods.

Today's economic reality will not be tommorrow's.

At some point of development the investment to move into Space will not seem as daunting as it does now. And at that point the reasons to go will not need to be as convincing as they are today.

It really depends on your definition of "plausible midfuture". If I were to say the "midfuture" is 100 years from now, its very possible the economic realities would largely ressemble today's

But if I were to say the "midfuture" is 10,000 years from now. Well then its quite possible there would be plenty of ways to accomplish a viable space based economy.

Re: SA Phil

I think the midfuture Rick is talking about is up to 2-300 years. 10,000 years is twice as long as we've had written history.

In any case, your economic argument doesn't hold water. Being relatively poor in the developed world may not be all that bad, but there is still real, abject poverty in the world. A man living in the streets of Mobasa, Kenya, stevedoring at the docks for a wage barely adequate to feed himself, is in essentially the same economic condition as a slave unloading wheat in Piraeus, 2500 years ago. He's an economic slave, not a chattel, but his physical condition and future outlook is no better.

Our highest technology is a very narrow peak, sitting on a very wide base -- and it always has been. Barring an unprecedented technological and economic revolution, that's not likely to change any time in the next several millenia, at least. Yes, more and more people will go into space, but they will be few indeed, compared to the rest of the human race.

(SA Phil)

Perhaps its your perception of my argument that does not hold water - rather than my actual argument.

Of course there are examples of poverty that have not changed much in 2500 years.

However instead focus on a country like the United States, where the working poor might live in a 1500 square foot house, have a car, have a 3000 calorie a day diet, etc.

That person could definitely be poor - he may even strenuously work more hours per year than the slave you mentioned. But the floor has been risen up by the prevalence of technology.

It would not be necessary for the whole world to be at that level for the economic realities to change.

How many millions of people fly on airplanes today?

What happens when space planes reach that level of mundane pervasiveness?

(SA Phil)

Look at our current lift technology --

What are the limitations?

Complexity - making rockets is specialized and complex

Exotic fuels - there is no Hydrogen economy.

Those drive cost. We obviously can afford those costs better than we could 50 years ago. We have a worldwide telecommunications system based on orbital satellites.

Change the technical realities and in your future economy - the costs go down.

At the same time the ability to afford those costs go up based on the size of the overall economy.

Tony

10,000 years is twice as long as we've had written history.

--------------

(SA Phil)

But that is only an artificial limitation in the bounds of a conversation. It is entirely plausible that:

A) Humanity will still be here 10,000 years from now.

B) It might take that long for us to develop a compelling reason to colonize space.

'Midfuture' is admittedly one of the most slippery terms I use. (Even more than 'plausible!')

Tony is essentially right that I mean within the next 200-300 years, at most maybe the next 500 years. Looked at a slightly different way, I'm talking about techlevels that are broadly recognizable - certainly not Clarketech.

For example, the midcentury space tech that I call rocketpunk has a clear recognizable similarity to our actual space tech 50 years later. At least so far as vehicle hardware is concerned - the electronics are a different matter. (But we don't have HAL, or Asimovian robots.)

I suspect that if we had spent twice as much on NASA in the post-Apollo era we'd have a good deal more than twice as much Cool Stuff, because less constrained budgets would have allowed less compromised designs and planning.

(Of course this is sheer speculation!)

So far, private initiatives have done essentially nothing in space - private industry does essentially all the metal bending, at any rate in the US, but the initiative is all public. It will almost certainly remain that way for some time to come, absent a really huge and very unexpected tech revolution.

Ferrell's analogy to Antarctica is to the point here. I don't know how much is spent on Antarctica, but worldwide it is probably in the low billions, judging from the scale of activity.

What might happen on the scale of 10,000 years is a whole 'nother matter. It is perfectly possible to believe that our long term future in space is profoundly important, while regarding current era space programs as a mission to Vinland, irrelevant in the long run.

I don't think that is the case, but it is a coherent position.

(SA Phil)

Its possible that 10,000 years from now technology will appear a lot less "Magic" to us than many think.

A few hundred years ago we had a very limited understanding of science. That is not the case now.

I think the final technological Irony will be that we are now more relatively advanced compared to our ancestors of 10,000 years ago...

Than our descendants 10,000 years in the future will be compared to us.

-----------

I think the largest difference will be the availability of Energy. And that will do a lot to change economics and the economics of Space Travel.

To a lesser extent that will probably be the case 200 years from now as well.

I think the final technological Irony will be that we are now more relatively advanced compared to our ancestors of 10,000 years ago...

Than our descendants 10,000 years in the future will be compared to us.

I could run with that idea in a story and believe it but in terms of actual prognostication, it doesn't ring true. This is gut reaction, not reasoned science, naturally. If we consider hunter-gatherers versus us today, for as big a leap in the future I'd say the handful of technologies would be the end of disease, biological immortality, and a completely roboticized workforce so that any labor humans engage in would be for art and desire, not necessity.

That's a good question, though. What would the rest of you demand as futuretech to accept the statement "12011 AD is as advanced beyond 2011 AD as 2011 AD is beyond 7989 BC"?

"Steve Squyres, the principle investigator on the Mars Exploration Rover program has said more than once that a human on-site could have done more in minutes than the MER rovers did in days. Once again, the scientists only put up with robotic probes because economics keep them from going themselves. If the economics changed even a little bit, scientists would drop proposals for robotic probes and start polishing up their CVs with science crew selection in mind."

Good.

Makes a nice change from the usual "evidence" signifying the superiority of robots over humans.......

(SA Phil)

Jollyreaper,

I would definitely think Bilogical immortality would be one that would qualify.

I just think that it is as unlikely as FTL travel.

One of those technologies that sounds great, but may never actually be feasible.

It might be probable through whatever means to extend life several decades on average.

But at that point you aren't really doing anything we didnt already do vis-a-vis 10,000 BC

Upon reflecting, I do have a thought. They have sailing ships pulled from the mud in Israel that are pretty much the same as wooden boats today. There's a lot of fiberglass in use even though some people build woodies but in terms of shape, outline, etc, an ancient fisherman would find himself right at home and glory in having a fish finder, GPS, and weather radio.

We haven't really done much to improve on the knife. Better materials, more durable, but it's the same basic idea. Not much has gone on with firearms in the last 50 years. Better scopes, better materials, but they're still firing bullets. No laser beams and fancy stuff. But developments happen in other ways.

You get back to the question of how to depict a door in scifi. 200 years from now, we assume they'll all be automatic but wait a second, why would they be? A hinge and doorknob is pretty nice. How would you really improve on that? Maybe people decide they like pocket doors more, the kind that slide instead of swing. It's not like we don't already know what those look like. And they operate by hand.

The doors might not change. What's inside the room could be very interesting.

I think that we haven't even begun to scratch the surface of what's possible with bio-engineering. We already know that some animals can manage immortality like certain kinds of jellyfish. I would not put human immortality in the same category as FTL. I'd put it between moon colonies (yes, we could technically do it, but would we do it?) and FTL (we don't even know if physics allows for it.) It's more like resurrecting extinct species. We hypothetically know how we could do it, intelligent and reasonable scientists can be on either side of the debate and it's not cloud cuckooland. That's not staking a claim it will or won't happen, just that it's a reasonable thing to speculate about.

SA Phil:

"Perhaps its your perception of my argument that does not hold water - rather than my actual argument.

Of course there are examples of poverty that have not changed much in 2500 years.

However instead focus on a country like the United States...

It would not be necessary for the whole world to be at that level for the economic realities to change.

How many millions of people fly on airplanes today?

What happens when space planes reach that level of mundane pervasiveness?"

But they won't, because space planes with chemical rocketry are a fantasy. You have to assert speculative tech like fusion or even gravity control to lower costs to the point that the average, or even above-average-but-not-filthy-rich, could participate in space flight.

"Look at our current lift technology --

What are the limitations?

Complexity - making rockets is specialized and complex"

Jet airliners are demonstrably more complex, and they come out of essentially the same tech tree (large, pressurized aluminum structures, propelled by reaction jet engines).

"Exotic fuels - there is no Hydrogen economy."

Most liquid fueld rockets use kerosene. The first stage of both the Saturn V and Saturn IB launch vehicles, the Soyuz, the Atlas, and the Falcon all qualify. The liquid oxygen used as an oxidizer is a standard industrial chemical. You can whip out your cell phone right now and order some from any industrial gas supplier. And, strangely enough, though LOX/LH2 engines like the SSME have a higher rated specific impulse, if you count the mass of the tankage and other airframe components, LOX/Kerosene is actually the more efficient propellant combination.

Also, the chemicals used in hypergolic uper stages may be nasty, but they are hardly exotic either.

Hydrogen is only used in rockets when there's a specific technical reason to use it. Plenty of launch vehicles do with only one hydrogen stage, or none at all.

"Those drive cost. We obviously can afford those costs better than we could 50 years ago. We have a worldwide telecommunications system based on orbital satellites."

What drives the cost more than anything else is the low demand combined with the limitations of the technology. There's just not a lot of things people can do in space using chemical rocketry. And the costs, in constant dollars, haven't gone down noticeably. Miniaturization of electronics has allowed us to put more and more stuff on a constant sized satellite chasis, that's all. You can't miniaturize people.

"Change the technical realities and in your future economy - the costs go down."

Fine, change the technical realities. But you can't handwave that change. Do you have a specific plan that doesn't involve chemical rocketry (because we've advanced that about as far as it will go)?

"At the same time the ability to afford those costs go up based on the size of the overall economy."

The figure of merit isn't the absolute size of the economy, but the size of the economy per capita. That looks to remain constant for a long time into the future, barring a revolutionary change in our ability to generate energy.

Tony:

I think we could do more with chemical rockets if the price came down. The problem right now is that the price is too high to do more than we already are, and the lack of new interest is driving away R&D dollars. If we could change that, we might be able to do a lot more.

And fusion won't help, except to bring the cost of energy down.

Byron:

"I think we could do more with chemical rockets if the price came down. The problem right now is that the price is too high to do more than we already are, and the lack of new interest is driving away R&D dollars. If we could change that, we might be able to do a lot more."

I wish I had a buck for every time I've heard that assertion in the last 20 years. It's simply not true that chemical rocketry can be much further refined. The SSME was within a percent or two of the theoretical maximum performance for a LOX/LH2 engine thirty years ago. The engines used on the Soyuz haven't seen significant performance improvement in over 50 years. And at the current level of refinement, the price meets the demand.

"And fusion won't help, except to bring the cost of energy down."

Obviously I'm talking about operatic levels of fusion reactor performance and compactness.

Tony:

I suggest you look up OTRAG. There are things we can do to reduce launch costs without improving technology. It won't be as cheap as current jets, say, but it will be less expensive.

Tony:

"space planes with chemical rocketry are a fantasy."

True

"You have to assert speculative tech like fusion or even gravity control"

The "microwave thermal rocket" http://www.astrobio.net/exclusive/3747/beaming-rockets-into-space (Google it for more references) is a much more plausible than gravity control method for getting into orbit at a reasonable cost.

If the propellant is hydrogen the exhaust speed is almost twice the best chemical rocket, so a single stage to orbit space plane becomes doable with this tech.

There is still the chicken vs. egg issue of having enough demand to justify building the infrastructure, but it's nowhere near as bad as for the space elevator or launch loop.

(SA Phil)

(RE to Tony on Chem rockets)

The efficiencies might be close to the theroetical maximum...

However the costs are far from their theoretical minimum.

Substitute "cheap, reliable one shot rockets" for space plane if the term bothers you - it really isn't a distinction that invalidates the idea.

The point is the costs could be a lot less than they are.

-------

-------

Hydrogen is the most efficient propellant- but not the easiest to use. That changes with technology of course.. And a hydrogen economy.

Hydrogen is even better with the laser thermal, etc. ideas.

Byron:

"I suggest you look up OTRAG. There are things we can do to reduce launch costs without improving technology. It won't be as cheap as current jets, say, but it will be less expensive."

Hey, from now on, let's assume that I know about anything in rocketry you care to mention. Please try to phrase your challenges to my knowledge as questions, e.g.:

Tony, bubbi...what do you think about OTRAG?

What do I think about OTRAG? It was a neat idea for very small payloads, but the massive clusters they were proposing to launch serious payload masses could never have been made sufficiently reliable without massive improvements in quality, leading to massive increases in costs. As always, TANSTAAFL.

Jim Baerg:

"The "microwave thermal rocket"...

There is still the chicken vs. egg issue of having enough demand to justify building the infrastructure, but it's nowhere near as bad as for the space elevator or launch loop."

All of these things, even the most entry-level, least expensive ones, are based on exponentially higher demand than presently exists. There's just no way to make people in space pay, at any level of investment.

SA Phil:

"The efficiencies might be close to the theroetical maximum...

However the costs are far from their theoretical minimum.

Substitute "cheap, reliable one shot rockets" for space plane if the term bothers you - it really isn't a distinction that invalidates the idea.

The point is the costs could be a lot less than they are."

No they couldn't -- no demand exists to cause lowered costs. The theoretical minimum only exists after a huge infrastructure investment that simply isn't justified. So whatever the theoretically low cost may be, we've reached the practical minimum costs.

"Hydrogen is the most efficient propellant- but not the easiest to use. That changes with technology of course.. And a hydrogen economy.

Hydrogen is even better with the laser thermal, etc. ideas."

In rocketry terms, hydrogen is the most efficient reaction mass. The problem is not making it. It could be made reasonably inexpensively if there was enough demand for it, whatever other fuels the rest of the economy happens to use.

But you have to heat it somehow. It turns out that nuclear fission heating can't even make an Earth launch vehicle, because it's just not heat-intensive enough. Barring cheap, light, flight qualified fusion reactors, you have to use beamed power. But beamed power runs into the infrastructure expense problem already discussed. It also can't lift payloads greater than 5 or so tons. So you would have to establish an on-orbit infrastructure to collect and process all of those small palyloads, and further infrastructure to assemble the payload contents into useful large structures.

Once again, the theoretical is so far beyond the practical that I wouldn't hold my breath.

(SA Phil)

Tony,

I am not sure "demand" is actually what you mean here. In any case you are using the term like a phlebotenium to win your arguement.

--essentially----

1)There will not be extensive demand of chemical rockets due to high costs.

2)Costs wont go down until there sufficient demand.

---???-----------

In reality demand drives prices up, supply drives them down.

Demand can only drives prices down inderectly - IE by people thiniking they can make a big profit and thus increasing supply.

----------

What is really going on is that there is no economy of scale. And that the lack thereof is its own hinderance.

But that changes with your technology. If you bring prices down through other means (technology) or scale up (larger economy) You can drive the scale upwards. Then Supply goes up. Prices go down further. The cycle repeats and pretty soon you have a real industry.

Tony

But you have to heat it somehow. It turns out that nuclear fission heating can't even make an Earth launch vehicle,

---------------

Whoa -- sure you can. The radiation is the drawback, not the launch physics.

They already designed one. The Dumbo (competitor to NERVA) had a T/W >1

(SA Phil)

(SA Phil)

Tony,

I am not sure "demand" is actually what you mean here. In any case you are using the term like a phlebotenium to win your arguement.

--essentially----

1)There will not be extensive demand of chemical rockets due to high costs.

2)Costs wont go down until there sufficient demand.

---???-----------

In reality demand drives prices up, supply drives them down.

Demand can only drives prices down inderectly - IE by people thiniking they can make a big profit and thus increasing supply.

----------

What is really going on is that there is no economy of scale. And that the lack thereof is its own hinderance.

But that changes with your technology. If you bring prices down through other means (technology) or scale up (larger economy) You can drive the scale upwards. Then Supply goes up. Prices go down further. The cycle repeats and pretty soon you have a real industry.

May 17, 2011 1:25 PM

Anonymous said...

Tony

But you have to heat it somehow. It turns out that nuclear fission heating can't even make an Earth launch vehicle,

---------------

Whoa -- sure you can. The radiation is the drawback, not the launch physics.

They already designed one. The Dumbo (competitor to NERVA) had a T/W >1

SA Phil:

"I am not sure "demand" is actually what you mean here. In any case you are using the term like a phlebotenium to win your arguement.

--essentially----

1)There will not be extensive demand of chemical rockets due to high costs.

2)Costs wont go down until there sufficient demand.

---???-----------

In reality demand drives prices up, supply drives them down.

Demand can only drives prices down inderectly - IE by people thiniking they can make a big profit and thus increasing supply.

"

You're thinking of the economics of existing products and existing consumers. I'm talking about the economics of needing a threshold demand level to motivate investment in infrastructure costs. You don't build a four lane highway out to Farmer John's place. You may not even extend a paved road. You do build a major highway between Las Vegas and Los Angeles.

In space launch, you don't build a huge launch infrastructure (of any type) if your total global demand demand is a few dozen payload tons a year.

"What is really going on is that there is no economy of scale. And that the lack thereof is its own hinderance.

But that changes with your technology. If you bring prices down through other means (technology) or scale up (larger economy) You can drive the scale upwards. Then Supply goes up. Prices go down further. The cycle repeats and pretty soon you have a real industry."

You have to have a threshold demand to get the ball rolling. Once again, that demand simply does not exist.

"Whoa -- sure you can. The radiation is the drawback, not the launch physics.

They already designed one. The Dumbo (competitor to NERVA) had a T/W >1"

The t/w ratio is calculated from the engine thrust and the engine weight. The figure of meirt is engine thrust to vehicle weight. For example, the NERVA had a t/w ~= 7.5; a representative LOX/Kerosene engine, the LR89-7, used on the Atlas, had a t/w ~= 136.

Tony,

I dodnt say NERVA, I clearly said Dumbo.

There is a big difference in thrust to weight between the two designs.

By T/W >1 I mean that it is capable of lift off. Below 1 and it is not.

I doubt very much you are using the same units that I was in the T/W calculations you give there.

(SA Phil)

(SA Phil)

Tony,

As to the "demand" claims you make here -- assume your demand goes up, then what?

SA phil:

"I dodnt say NERVA, I clearly said Dumbo.

There is a big difference in thrust to weight between the two designs.

By T/W >1 I mean that it is capable of lift off. Below 1 and it is not.

I doubt very much you are using the same units that I was in the T/W calculations you give there."

I used the performance figures given in Encyclopedia Astronautica, which should be good enough for anybody. Also, a t/w ratio is a dimensionless number. Units are irrelevant.

As for a vehicular t/w ratio, what vehicle, under what circumstances, with what payload?

"As to the "demand" claims you make here -- assume your demand goes up, then what?"

What makes the demand go up? There's nothing for people to do in space except explore. It doesn't take a lot of people to do that, nor a lot of mass in spaceships and consumables. Where is the demand for multitrillion dollar infrastructure investments going to come from?

Tony, leaving negative replies behind, what would you do to improve the economy of the space launch delimma (high cost/low demand)? Does anybody else have some ideas? Mine are reduction of overhead and reduction of high-cost materials for the fabraction of the rocket bodies. Exploring novel launch methods to see if any of them lead to lowering costs should also be looked into.

Ferrell

Real space spending has increased:

http://james-nicoll.livejournal.com/2857987.html

and simplistic trend extrapolation suggests Mars in 2090. And there's an almost overwhelming variety of active probes:

http://www.planetary.org/blog/article/00002983/