Starship Troopers Gets a Dozen at the Grating

"Bugs, Mr. Rico! Zillions of 'em!"

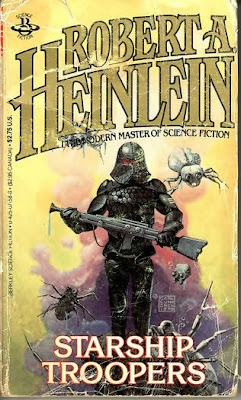

This is a commentary on the Robert Heinlein novel in which those immortal words appear, not the Paul Verhoeven movie in which (unaccountably) they are never spoken.

I like Starship Troopers, the book, but do not entirely approve of it. This itself is an odd thing to say. Quite apart from whether anyone else cares what I approve of, it is not the way I or most people usually talk about science fiction novels. But people do not talk about Starship Troopers the way they do about other SF novels, and I am not going to either.

Let's cut to the chase. The Starship Troopers debate, and it is as old as the book, is mainly about the Federation's political system and military institutions, and the surrounding culture, as shown in the book. What does Heinlein think of them, and what should we think of them? In other words the argument is about the book's politics.

Should it even matter? Starship Troopers is a science fiction novel, a work of Romance. It takes place in an imaginary future that is NOT a thinly veiled stand-in for Heinlein's present day, nor an overt commentary on it. There is one oblique reference to the Korean War - an important one, dealing with the non-return of POWs, in a book where 'making pickup' on your troops is a major theme. But Heinlein is disciplined in his historical references.

I can infer that the war which led to creation of the Federation was fought against Communists, and especially those prisoner-waterboarding Red Chinese. But this is only an inference: Heinlein does not say it. I can read the Bugs as a metaphor for Communism, but the same is true of the giant ants in Them! Hey, it was the 1950s.

Heinlein's 1950s juveniles were his Golden Age, and he put a lot of sophisticated political commentary into them, from multiple perspectives. ('Murrican perspectives, naturally, though he hints in some stories that the Anglosphere has re-coalesced into a new British Empire.) Starman Jones portrays a dystopian future of the New Deal, Between Planets a dystopian future of the internal security state.

Heinlein is far more approving of the society in Starship Troopers. Everyday civilian life, the little we see, is pretty colorless, pun intended. But there are no ration coupons, let alone conscript labor battalions or secret police.

In fact the comfortable dullness of Starship Trooper's civilian world is one more way that this book resembles Space Cadet. The compare & contrast is so crisp it is embarrassing. Matt Dodson goes to space Annapolis, Johnny Rico goes to space Camp Lejeune. Both sit through some lectures on the political theory behind the service they have joined. These lectures go down smoothly enough that teenage and preteen readers mostly didn't throw the books against the wall.

The Federation Space Patrol that Robert Heinlein has Cadet Dodson join, with all apparent sign of approval, is a one world, internationalist, global peacekeeping force under UN-esque auspices. Patrol officers are Blue Helmets with nuclear weapons, that they have used at least once against a city. This ought to be smoking hot stuff (so to speak), but no one argues about Space Patrol the way they argue about Starship Troopers.

That said, Heinlein goes much more into the political structure and ideals of the Starship Troopers Federation, again with apparent approval. And they are problematic. Heinlein is trying to square the circle of traditional republican civic responsibility and pure volunteerism, but the Federation's service-based restricted franchise could easily leave most of the people under its rule with no voice the government is obligated to hear.

If you are going to debate political theory this is a serious issue, but it hardly accounts for the visceral tone of so many Starship Troopers arguments.

Real world history explains some of it. The implied historical background of Space Cadet - the UN as a delicately veiled instrument of American hegemonism - was relegated to the hypothetical at the very start of the Cold War, as the print was drying on the first edition. The Patrol is the recognizable parent of Starfleet, but its politics have been relegated to an indefinite future.

The implied historical background of Starship Troopers - a West narrowly rescued from lawless streets and an un-won war - got a much longer run in 'Murrican popular political culture. Case in point, the references to unreturned POWs hit a historical and cultural chord. They make Johnny Rico a second cousin to Rambo, albeit a few generations removed. He needs that power armor, to carry not only a buddy but also a lot of political baggage.

Which still doesn't quite explain the accusation that Starship Troopers is authoritarian, or worse. On substantive grounds the accusation is lame. Military recruit training is authoritarian, but if you want out, just say the word and you're on your way home. Only if you violated a military regulation do you stand to get a flogging on the way out the door.

But flogging is rather prominent in Starship Troopers. It brought forth Thomas M. Disch's notorious comment about 'swaggering leather boys,' and not until David Feintuch would there again be so much spanking in a science fiction novel. Floggings are not confined to the military, either. Johnny Rico reflects that if anyone carried on like a juvenile delinquent in the bad old days, he and his father would both get one. I guess Heinlein was not a big fan of Rebel Without a Cause.

Flogging, I believe, largely accounts for the whiff of authoritarianism that clings to Starship Troopers in spite of all merely logical objections.

In mainstream Romance we usually encounter flogging only in premodern settings, most often at the grating of an 18th century frigate. Wherever we encounter it, it symbolizes dominance, submission, and hierarchy. In a future setting, where there isn't even the element of historical period color, the connotations are that much starker.

The floggings even account, in a way, for the charge of fascism. Yes, that word is far past its sell-by date, and should be confined to political movements that feature color coded shirts, torchlight parades, and preferably some actual historical link to Benito Mussolini. But one thing that has entered the pop culture is that fascists and their ilk (especially You Know Who), were pretty kinky. Starship Troopers doesn't have chains or leather, but it does have whips.

Well, now I have talked myself into an awkward jam, haven't I? Because in spite of all this I still like the book. It's a great story, told by a great storyteller near his prime. It may show the first stages of Heinlein's later crankishness, but it isn't pulled down by them.

And I am not alone. The Starship Troopers argument has lasted so long because it draws its oxygen from all those conflicted readers who like it, even though they feel uneasy about it. Or vice versa.

Discuss.

76 comments:

Johnny Rico lives in a messed up society. We have to figure this out for ourselves because the book is in first person, making him, by definition, an unreliable narrator. Heinlein might broadly share his views, but the point is that we only see Rico's highly subjective point of view.

The authoritarianism of military training is fine in a society like ours where it's mostly volunteer (though there are some economic issues that put undue pressure on the working class to enlist). But the book makes clear that in order to be a citizen in this world, you must endure this horrific training regimen and, if you succeed, wage a xenocidal war of extermination. If you drop out, not only do you cease to be a citizen but lose any chance of ever becoming one.

The rulers of the society are therefore a cabal of those people, probably mostly men, who have endured this brutal ordeal but have been taught from an early age and through their training that it alone makes them worthy citizens of the republic. There is accordingly very little diversity among the ruling class, and no bottom-up pressure from below. Without reforms to this system of government, these sort of people will remain in exclusive power for generations, calcifying the militarism with a healthy dose of conservative, elderly stubbornness.

Fascist? I wouldn't use that word, but something like it. They're militaristic, unequal, and genocidal. The individual must be surrendered entirely to the state in order to become an individual in the first place. They're more democratic than fascists, but not much.

Perhaps the Bugs can't be reasoned with. Perhaps, though this doesn't necessarily follow, there is no choice but to wipe them out. But in a society such as the one that rules Earth in Starship Troopers, the same is true of the Apes.

I don't have time right now to dig into a fully thought out response to both the post and MRig's comment, but I wanted to point out something:

Heinlein VERY much believed that it was the nature of successful species to eliminate one another. He makes no bones about it: there's no room for both the Apes and the Bugs in the galaxy.

It's not a very uplifting view, admittedly, but it's not one without a sense of heavy pessimistic realism to it.

The biggest problem we encounter with the grand thought experiments that constitute politically-themed novels is that they are ultimately an elaborate hypothesis that is never really put to a test. As any scientist or engineer will tell you, the real world test can be a humbling thing. But often times proponents of these ideas will swear they work and point to the novel as an example of how successful they might be!

Ultimately, we end up like two generals chaffing under the boredom of a long, glorious peace. The technology has progressed, new tactics have been developed, they find each other as vociferous opponents in on the debate of which method is superior. And that question cannot possibly be settled definitely without trial in a proper war. But even if the use of the first set of tactics leads to crushing defeat, proponents may not be willing to abandon those tactics, arguing that the failure was not in the tactics but in not applying them more vigorously!

Having said that, I'll make my own unfounded thought experiment claim. I think there was some quote from Greek drama about how the source of tragedy for a great man will be related to his strength. I think something like that can be said for forms of government. The elements that give it strength will eventually rot and become the cause of downfall. But I will also say that any piece of machinery will fail for lack of maintenance. You don't blame the machine for the mechanic's lack of diligence.

I can see how a system like Heinlein proposed might work successfully and I can see how it might eventually fall to pieces in time.

whoops, forgot to flag for email follow up. :)

I haven't read the book in ages, but I'm pretty sure that military service is explicitly not the only kind of public service to qualify one for the franchise — and non-citizens have full property rights, etc. They're not helots.

You've captured my enthusiastic ambivalence quite nicely- I can't think of any other book I probably read four or five times from the age of nine that I'm still not sure I like, per se.

Its relative thematic simplicity is the source of a lot of both my enjoyment and consternation. Golden Age SF was, by and large, the enshrinement of the first-approximation thought experiment- the brainy late-night beer conversations about social issues stretched to a few hundred though provoking but ultimately simplistic pages. We're presented with a civilization that has a political culture ostensibly predicated on a strong culture of volunteerism and civil service (yay!) with a mechanism to try to avert moral hazard through selective enfranchisement (interesting, but for Heinlein to understand why conscription was bad and not why universal sufferage is good, eh....) that maintains its status through constant warfare in support some trumped-up, vaguely racist wannabe-Malthusian imperative (ick ick ick and demonstrably wrong to boot)- and that whole package, from the admirable ideal to the horrific implications, is presented as one big-easy to swallow male-bonding pill, wholly without irony or nuance. Selective enfranchisement with a military focus is functionally just about feudalism, and while Dune, for instance, is laden with feudal cultures I wouldn't be keen to live in, I never had the unsettling feeling that the characters hadn't noticed the cracks in the facade and were trying to sell it to me- in the later sequels, quite the contrary.

It might be that the book is such crack for nine-year olds, like myself, complete with coming of age tales, easy-to-find places for misfits in a grand scheme, and let's face it, awesome robot suits with nuclear bazookas, and simultaneously is laden with straight-faced lectures about why democracies suck and we must expand over our neighbors or die, that I get a little restless. It's a no more reprehensible society than any of a thousand sword-and-dragons monarchies that fill other kids books, but I can't remember any of those explaining why anyone who wasn't a knight sucked or, once again, having robot suits.

Ultimately, anyone with half a brain can compartmentalize- I walked away with some food for thought about moral hazard, civic responsibility, and dreams of orbital skydiving, and shrugged off the rest as fiction. That need to compartmentalize, though, is one more demand placed on a reader, and one more question raised about the author, with answers you might not like- it's a cost you may or may not be willing and able to pay.

@ Isegoria: They are. Heinlein later stated that there were non-military paths to the franchise in Starship Troopers, but every possible service mentioned in the novel itself is military. Truck driver, clerk, doctor, etc, are all mentioned in the options for Rico's military service, with no hint that they're a civilian service. In this point he reminds me a bit of Gene Roddenberry, who created a military starship undertaking 'police actions' against various enemy states - And then spent decades claiming that Starfleet was not intended to be a military service.

Here's Alexei Panshin's thoughts on Starship Troopers and Heinlein in general:

http://www.enter.net/~torve/critics/HeinleinRoP/ropcontents.html

Ian_M

I have to admit that I haven't read the book for quite so time; however, I do remember several things about it.

1. I don't remember the book being quite so overtly fascist as the movie...in the book, it was implied that retired military officers formed the civil government, but the movie made it seem as though the military High Command ran things.

2. Rico's high school civics class thesis involved all human conflict (i.e. warfare), was the result of population pressure...intresting, but most likely not true except in just a few instances; rather it may be a contributing factor. RAH seems to have put this in just to justify the reason he gave for the mutially genicidal war the Humans and Bugs were waging against each other.

3. In the here-and-now, there is no such thing as "nonjudicial punishment" in the civilian world; however, there is in the military. In the world of "Starship Troopers" civilians ARE subjected to nonjudicial punishment and one of these happens to be flogging. As a punishment for something like a DUI that does not involve an injury or fatality, it may be an effective form of deterrence against antisocial behaivor, but I wouldn't want to like in either the book or movie version of "Starship Toopers" world.

4. The world of ST is an ugly, grim, highly regimented world that is so pervasive that Johnny Rico has no clue (except in retrospect) that he is a subject of the state, not a citizen. His father does, but resists joining the 'ruling' class until he loses everything to the war. Johnny is typical in his desire to defend his homeland from an enemy and to satisfy his need for excitement by joining the military. It isn't until later in life that he starts to think there might be different ways to resolve relations with the Bugs besides exterminating them. That the whole story is told in retrospect lets some of that creep into the naritive, but in undertone. I think that that basic dictomy is what causes readers to have such mixed feelings about it; it's like the songs from the 60's and 70's I like to listen to, but don't agree with.

Ferrell

Welcome to new commenters!

Civilians in Starship Troopers apparently have civil rights, but no political rights to back them up. American experience both before and after Heinlein wrote shows how closely they are bound together.

From what we see in the book, elite civilians - Johnny Rico's father, and a doctor at the recruitment center - are fat, dumb, and happy. The only non elite civilians we meet are those merchant sailors, who do seem to have a beef with the system. But they don't get a lot of dialogue.

On aliens and wars of extermination, Heinlein didn't always seem to believe that. In Have Spacesuit, Will Travel he pretty explicitly offers an alternative. Which is - wait for it - a cosmic polyracial UN, that sometimes does whack races Patrol style.

Heinlein was complex. And my take is that earlier on he embraced his own complexity. In the juveniles, by and large, he is worldly - which is part of what made them so great for young readers.

Later, paradoxically, he tried to make everything simple, and it became more and more artificial.

The Moon is a Harsh Mistress simply did not work for me. I probably didn't care for the politics, but I don't remember them. I liked Mycroft. But what I mostly remember, and disbelieved from the moment I met her, was that blatant imposter claiming she was Hazel Stone.

Meta meta meta, but none of the Golden Age trinity aged very well, did they? Heinlein got cranky, Clarke got vague, Asimov got tedious. And they were all three shamelessly cashing in on the fact that they could sell last year's Tashkent phone book if it had their name on it.

I thought The Moon is a Harsh Mistress was hilarious, when Heinlein's idea of an independent, liberated woman was a complete clueless ditz who relied on the men around her to get anywhere.

Part of the reason Starship Troopers has such a polarizing effect is it is a polemic neatly hidden inside a novel. For the less sophisticated reader (i.e. the juvenile audience it was written for) the polemic slips in unnoticed, even on later re reads I would often find myself reading a passage when the meaning of a previous passage or section suddenly burst forth from my subconscious (much like the Alien's arrival in the first movie, natch...).

Most critics have obviously failed to read the book, or are very careless readers. Heinlein clearly states most qualifying Federal Service jobs are not military at all (hard labour in a construction battalion is mentioned), and military support trades have equal footing with the MI. I suspect the main reason Heinlein chose Rico's federal service to be military was a setting in a construction battalion would be boring...

As well, the "Bug War" breaks out during Rico's basic training, so it is obviously implied that there are periods of peacetime service and peacetime veterans as well (picture the millions of service members who deployed in Europe during the Cold War, for example). The key element in Heinlein's formulation is the citizen in being demonstrates the willingness to sacrifice for the greater good.

If there is any weakness in the society, it is the huge imbalance between the numbers of "citizens" and "taxpayers". Since up to 80% of people on some planets are non participants in the political process, the vast majority of the production and wealth is not in the hands of the political citizen class.(BTW, this is close to the correctly political definition of Fascism; where the nominal ownership of assets is in private hands but the outcomes are determined by the State).

Jane Jacobs makes a clear argument for separating political from economic power in Systems of Survival (although this may not be what Heinlein had in mind).

In the long run this sort of society will lead to a situation where the productive class decides they are no longer willing to hand over their wealth to the elites. A sequel to Starship troopers where the masses rise against the elites would be interesting, they have the logistical base of society, but the elites have command of all military and police forces. Is it resolved through devolution to authoritarian rule, democratization or something else?

@ Thucydides: I've read ST repeatedly, I've read it recently, and I've read it carefully. In every instance where Rico considers a possible occupation within the Service, it is in a military context. When he's considering his Civics teacher's lessons, when he's at the recruitment centre, or when he goes in to sign up, all of the trappings are explicitly military. At no point does Rico or a Service representative say there is a civilian option. At no point do they say there isn't a civilian option, but again all of the scenes are explicitly military in character.

Construction companies aren't organized as battalions. The Peace Corps isn't organized into battalions. The US Army Corps of Engineers, on the other hand...

I do agree with your observations about Jane Jacobs and how her ethical system would apply to the ST setting. She would probably have considered the government shown in ST to be well on its way to stagnation if not epic levels of corruption.

'The Man Who Never Missed' by Steve Perry is one possible what-happens-next for the society in ST. It's the first book in Perry's Matador series, but it's one of those series where the first book neatly says everything that needs to be said. The rest of the books are just sex and violence.

Very good sex and violence, mind you. A lot of fun, but not really needed to make the point.

Ian_M

I had a fair-sized post typed up, but Thucydides stole most of my thunder. That's what comes from wandering away from your computer for a few hours. Oh well.

I do have one thing to add to what Thucydides has to say, though: Heinlein does, at one point, discuss the possibility of rebellion against the current status quo (I believe during Rico's OCS History and Moral Philosophy class). They point out that rebellion requires sacrifice -- the rebels must be willing to sacrifice their lives for the sake of the rebellion, if the rebellion is to succeed. Non-citizens are, by definition, not willing to make this sacrifice.

Whether this is true or not is certainly up for debate, but that's the argument Heinlein makes, and I think it holds up... assuming, at least, that the government doesn't piss off its non-citizens so much as to drive them to defend themselves against it -- which it shows no inclination to do.

And Ian snuck a post in on me while I was typing up my new one. While "civilian" may not be quite the right word (it's still federal service, after all) there are explicitly mentioned numerous non-military examples of federal service. Reread the part where Rico's signing up for service. The sergeant at the desk says:

"So for those who insist on serving their term -- but haven't go what we want and must have [for military service] -- we've had to think up a whole list of dirty, nasty, dangerous jobs [...] may wind up in Antarctica, eyes red from never seeing anything but artificial light and knuckles calloused from hard, dirty work. [...] digging tunnels on Luna or playing human guinea pig for new diseases."

There's also a part during his basic training where he mentions that merchant sailors have tried (although failed) to get their trade classified as federal service. Though no specific reason why it was rejected, it's never implied that it was because it was too "civilian" to count. I imagine that it simply wasn't dangerous/unpleasant enough.

So yeah. Basically what Thucydides said: many federal services are not military in nature. The military ones are simply the ones that Rico (and thus the story) cares about, which is why they get more attention. After Rico joins up but before he's placed in the M.I., we get this: "I didn't bother to list the various non-combat auxiliary corps [on my list of assignment preferences] because, if I wasn't picked for a combat corps, I didn't care whether they used me as an experimental animal or sent me as a laborer on the Terranizing of Venus -- either one was a booby prize."

"The sergeant at the desk says:"

Reread that scene. THE SERGEANT. Not a civil servant, A SERGEANT. A member of the military says that if you're not fit for fighting, we've got lots of other jobs for you.

Just because the non-combat roles are described as auxiliary corps does not mean they are non-military. The armed forces have auxiliary corps. Civilian groups don't group their logistics/support staff into corps, auxiliary or otherwise.

And the real military has lots of jobs that don't involve combat. Cooks, mail clerks, surgeons, truck drivers, mechanics... Are all non-combatants, non front-line troops, but still military. Heinlein did state after publication that he never intended for the Service to be a purely military service. But every scene that adresses the nature of Federal Service involves explicitly military personnel, discusses occupations that are found in the military, and states that the Service is organized along military ranks and divisions.

It's like arguing that Starfleet is a peaceful survey and exploration group... That just happens to be on the frontlines of every shooting war, is organized along naval lines, and has ships that carry enough firepower to sterilize a planet.

Ian_M

My impression is that Federal Service is essentially military. If you want to be a citizen, understand the oath, and are totally useless for any military role, they will assign you some sort of make-work. But it is not really an 'option,' just how the system handles recruits it has to accept but can't really use.

The problem with the small proportion of citizens (at least in some places) isn't just that economic assets are outside of the citizen class, but that most of the whole society is. A small, self-selected citizen class could easily become an oligarchy deeply alienated from the rest of society.

This is the subtle flaw in Heinlein's argument that the system is stable because the people who are warlike enough to become dangerous rebels can become citizens instead. What if they don't want to?

I guess it's a sign that the Internet has matured: I could predict almost exactly the comments that turned up in response to this post. Seen 'em all before. We've got the "Heinlein's-a-fascist" maneuver followed by the "it's not all military" parry, which devolve quickly into an "is not!" vs. "is too!" loop.

So let me say this: of course the society in ST is dominated by the military. That's the point. Heinlein is asking why anyone who isn't willing to die for their country should have any say in running it. It's a valid question, and calling him a fascist for asking it doesn't change that.

There's also a subtle "if this goes on" sting in his future history. The government in ST is military dominated because it was only military veterans who were both willing and able to pick up the pieces after the previous universal suffrage society imploded. In other words: if you don't take care of your country, and pay attention and contribute and do your part -- someone else will and you won't get any say in the matter.

This is the subtle flaw in Heinlein's argument that the system is stable because the people who are warlike enough to become dangerous rebels can become citizens instead. What if they don't want to?

Heinlein would probably contend that his model society in Starship Troopers is divided into sheep (productive taxpayers) and sheepdogs (the citizens); individuals who have the motivation to become dangerous rebels would be seen and treated as wolves.

So long as the oligarchy which runs the society doesn't become inbred (i.e all the new intake only comes from "military families"), alienated from society or otherwise ineffective, the "wolves" will not be able to assemble in packs large enough to cause a serious threat to society.

Cambias has distilled the essence of Heinlein's message in this novel (read enough Heinlein novels and you will realize he has lots of different messages):

if you don't take care of your country, and pay attention and contribute and do your part -- someone else will and you won't get any say in the matter.

Words to live by.

I'll sit next to Thucydides on this one.

The road to full citizenship in ST was community service and strictly volunteer; military service was a subset. Heinlein postulated that a person who isn't willing to give a few years of service to the society probably shouldn't be making decisions for the society.

As memory serves but doesn't reenlist, there were only two restrictions to community service, age (18 or older) and the mental ability to understand the contract.

Other than those, no one was refused. A 94 year old blind, deaf paraplegic could decide to obtain her franchise and she would be accepted. She'd be give a job (Heinlein wrote about counting by touch the hairs on catapillers in some lab) and at the end of the two year term - full citizenship.

Again from memory military service was a 20 year hitch. If booted for cause, no franchise.

A couple of thoughts about military service:

First, not everyone who serves is a fascist or an authoritian. I'm not; my husband isn't; my brother wasn't; I know Rick isn't. In fact the most radical far left wing near anarchist I ever met was a former USMC pilot. Most of us join for the same reason most people do most things -- at the time it seemed in our best interests to do so. Dwight Eisenhower was up front about why he went to West Point; he wanted the free college education which was otherwise unavailable to him.

Second, military training is not brain washing; it's behavorial modification. Keep in mind we have teenagers routinely dealing with stuff that can kill people and break things, some of it on a continental scale. Husband had just turned 18 and he was up close and personal with thermal nuclear warheads. It's in everyone's best interests to have them focused.

As I would tell my eager young space cadets, "I don't give a rat's ass what you're thinking; I am intensely interested in what you do. If you can't button a shirt correctly, I'm no way in hell letting you near an ICBM or my pay record."

Hell with the maturing Internet, I don't think the Starship Troopers argument has changed much since the only discussion threads were in zines printed on memeo paper.

The nature of Federal Service is a bit ambiguous, because there some tension between what Heinleins says and what he shows. But I'll stick with my 'essentially' military expression above.

The only requirement for citizenship is that you understand the oath. If you do, they will find something for you to do. But once you sign on the line, BuPers owns your ass. The possible billets Rico lists are all billets, all military.

In fairness there is also tension between social theorizing and writing a damn novel. Rico wanted to be a space pilot, not an inner city teacher, before he found himself in the MI instead.

(I think 20 years was if you went career, not just doing you hitch and getting the franchise with your honorable discharge.)

But the issue raised by a service-restricted franchise is really separate from the nature of the service. (And nonmilitary service could easily have quasi military features, e.g. Civilian Conservation Corps.)

The problem is that whatever form it takes, and however honorable the concept - service has deep roots in the republican tradition - a restrictive franchise still means a subject population, having no political voice.

Variations on this problem come up in all sorts of ways. For example, 'caucuses,' which produced a bit of ruckus during the 2008 US presidential primaries.

A caucus, for non 'Murricans, is a system of public meetings rather than a conventional election. Any eligible voter can show up, but you have to sit through a public meeting, elect a precinct chair, and so on.

The point is that this is sort of a 'micro-service' franchise, that requires significant effort, and thus commitment to the political process, to take part in. The upside is a more involved and informed electorate, people who care. The downside is that it is less representative of the broader public.

Heinlein's analogy to sheep and sheepdogs evokes a historical example he probably never thought of and certainly did not have in mind: Ottoman Turkey. Their term for their subject population was 'human flock,' and the Janisaries were their sheepdogs.

Slave soldiers are very alien to our Western traditions, and it is hard to imagine anything more alien to Robert Heinlein.

I was always under the assumption that Heinlein had set out to create the ultimate Switzerland, not the ultimate fascist state.

He started with the assumption: young men should be required to serve in the military.

Of course, to 'Murrican sensibilities, compulsory draft is very much a fresh wound. We simply are not a nation that views a draft as a good idea, so I think Heinlein injected some notion of making it optional.

Of course, this presents a problem...so he creates a Swiss-like society by requiring federal service for suffrage. In effect, to be a full member of society, you have to serve...the only real difference with Switzerland is that they don't throw you in jail (or whatever penalty compulsory service countries exact), they make it optional and remove certain rights.

The further sense I got from the novel is that the people who don't serve are generally apathetic to it...I get the sense that suffrage is simply not a priority in Heinlein's society by reason of the cost outstripping the benefit. It seems like the decisions of ST's world government don't really affect day to day business: the elite will stay "fat and happy" without needing to become active in government.

I think Heinlein's real failing in this whole debate was not expanding civilian life all that thoroughly...or the nature of the world government as it pertained to a citizen.

I'm curious...what do people think of countries that require military service of young people? I'll pick Switzerland here...the others I can think of off the top of my head are too politically charged.

Requiring military service (or any other form of service)is a form of slavery, and thus wrong in any case. I am pretty sure Heinlein is on message with that, and although my copy of ST isn't available, I recall a section after Rico goes "career" where they discuss military forces from the past and conclude that conscript troops, bureaucratic armies with huge tooth to tail ratios and armies which draw their officer class from different backgrounds than the troops are serious drains on the State's resources without providing the requisite amount of fighting power. In Heinlein's future history, these armies collapsed during the third or maybe fourth world war against China, leading to the breakdown of Western society and the evolution of the one Rico lives in.

Rico works in the all volunteer MI which (seemingly) has a 100% tooth ratio and draws all its leadership from the ranks, which instructors at OCS approvingly state is the best of all possible formations. I will leave it to others to debate if such things are even possible (an army with military tail still needs a tail of some sort; Heinlein never gets into a lot of detail on how this is accomplished).

Perhaps I wasn't clear about the "sheep and sheepdogs" analogy; in ST the sheepdogs are facing outward to fend off marauding wolves, Bugs and other unpleasant creatures, but there is no real reason given or implied that the sheepdogs couldn't turn and face inwards instead. Once again, Heinlein doesn't spend a great deal of time developing the culture and society enough for the readers to know and understand more than Johnny Rico does (and even at the end of the novel he is only a platoon commander, so how much knowledge and experience would he have to share with us?)

Starship Troopers is a very interesting thought experiment, and so long as the reader is willing to accept the basic premise that volunteer service is both sufficient and necessary to bind together a functional society

and also to see that there are weakness in the argument (particularly the self selection aspect; who is deciding what is the "greater good", are civil rights possible without political rights, and the potential alienation of some or most of society from the self selected), then readers have an enjoyable way of spending an evening or weekend reading and a lifetime of springboards for political discussions. Not bad for a "Juvenile" novel!

Stephen Pressfield wrote an excellent novel about Thermopylae called "Gates of Fire." It's a giant love letter to the Spartans. The novel starts immediately following the last stand of the 300. A lone survivor is found, a severely wounded helot. Xerxes wanted to know what manner of men he faced and ordered his translator to take down this greek's story, to know who he'd faced down.

The novel is told in a mixture of flashbacks detailing the helot's upbringing, what brought him to Sparta, and how he ended up among the 300. That storytelling is interspersed with the advancing of the Persian campaign and ultimate defeat and withdrawal.

The novel gets across the ideal the Spartans strove to live for. Of course, detractors will point out that the Spartans were merciless, brutal, starting wars and enslaving people. They are nothing like the Americanized ideal of a peaceful people minding their own business until some nasty power starts a war that the good guys will finish.

It's a question for the historians as to whether Sparta at any given time lived up to the ideals touted by contemporary poets and conferred by admirers throughout history. I know some history buffs who considered them nazis in togas and that they were never anything but, there wasn't a damn thing good you could say about them.

It might be grounds for a flame war but I think a very interesting discussion could be had concerning the official and heroic history of America, as approved by the Texas Board of Education, versus the unvarnished reality. Too many people might have dogs in that fight, of course. But there's the way things were supposed to work in this country and the way things did. But people looking back with rose-colored glasses will see history in the context of the theory rather than the reality. It makes me wonder how accurate Rico's perception of his own society is. After all, a nobleman's son and a peasant's son can both grow up in the same society and have vastly different experiences and thus different opinions on just how good it is.

If we accept Heinlein's premise that this is a most excellent society and everything is working to the ideals that OCS described, how long will it last? What happens when external threats are swept away, if no new bug rages are encountered, when a Pax Terra extends over the known galaxy? How long until the society starts to devour itself? When do they hit imperial overreach? And in a weakened state, will there be a new bug race looking to take over the weakly defended planets of Man?

The part about the MI and their 100 percent tooth ratio is pure BS, on either Johnny Rico's part or Heinlein's. Although he modeled them tactically on paratroops, strategically they are gyrenes, and the entire Federation Navy is their tail.

Is Johnny Rico an unreliable narrator? I generally don't think of Heinlein as an unreliable narrator kinda author, but you can take a straight shot of PoMo and say that this is beyond the author's control.

I was always under the assumption that Heinlein had set out to create the ultimate Switzerland, not the ultimate fascist state.

Early finalist for insight of the week. But Heinlein wants a war story, which makes them a bit more like the 16th century Swiss than modern ones.

All in all Heinlein has only himself to blame for the controversial reception, which is sort of the point of my original post. He gives us a political theory based on a service elite AND a racial war of extermination AND those floggings. They are not really much connected to each other, but together they are kind of explosive stuff.

Having said that, the political and social commentary in this book is actually pretty sketchy, a couple of pages of H&MI lecture notes amid 250 pages of Xtreme summer camp interspersed with cool SF combat.

Which makes it all the funnier that we argue endlessly about it.

On mandatory military service: a couple thoughts:

1: On one hand if I should have to risk my precious life (precious to me anyhow) so should the next guy. -but on the other hand some people are good at farming, some people are good at business, some people are good at politics, some people are good at art and some people are good at the art of war: Why pollute a willing competent army with unwilling and/or incompetent individuals (incompetent at least in the art of war)?

2: If there was mandatory service I would have the age much higher so one can first come to some sort of understanding of oneself, the world around them, and what they would be potentially fighting, killing, and dying for. The world is so complex with opposing religions, political systems, economic systems, social systems, etc.: How can one possibly know who or what they should or shouldn’t be fighting for at the age of 18 or 21 especially when forced? I would put the mandatory age (at peace time) at least at somewhere between 23-27 and that still maybe too young, perhaps between 29-33 would be better; you can serve earlier, you just have to eventually serve. If you put Hitler’s regime in England and Chamberlain’s/Churchill’s government in Germany in the 1930/40’s: How many soldiers on either side would disobey their orders because of a moral obligation? When your young and dumb you do what people tell you, and that makes you potentially dangerous. -but then again maybe that’s why they want to get you so young: So you won’t think the grass is greener on the other side of the war!

That's precisely the reason they want them young. In WWI they had Christmas truces at the beginning where the soldiers would stop fighting and socialize on no-man's-ground. The generals on both sides were horrified. How could they have a proper war if the young men refused to fight each other like good little thralls? So they put a stop to that right quick.

The French faced rebellion amongst their troops. " The mutinies "were not a refusal of war" simply "a certain way of waging it"." The French conceded some of the points of the mutineers but executed over 700 men for cowardice over the course of the war.

It's not just the military. You see senior workers let go and replaced with hires fresh from college. Why? Kids are easier to cow and BS than men who have been around the block. Kids are trying to impress and have no idea how badly they're being taken advantage of.

Aside that the comment I deleted a little ways upthread was mere garden variety spam, rather than topical but intemperate.

On conscription, does anyone really believe that the Federation would not ignore its principles and resort to a draft, if survival were at stake and a draft would help?

Flip side: Heinlein lived in an age of mass armies, but he is describing a world where the mass army is obsolete. Most Federal Service would probably be civilian (which is what he claims, but not what he shows), simply because the military has limited billets. MI are very expensive to recruit, train, equip, and deploy, and the space navy can only use so many mess cooks.

Armies are raised to fight, not think (beyond what is needed for effective fighting). The traditional 18 year old recruit is approaching physical prime; a 27 year old would be past it. And 18 year olds are not only naive, they are also less attached to anyone or anything outside the army.

Note that the modern US military has collided with 'Murrican working class culture in a way that produces a large proportion of married troops with families. One consequence is that 'nursery officer' is no joke. If you have small kids on post, an officer had better be responsible for them.

Since they are mentioned upthread, by the way, I once said a bit about the Spartans on this blog.

Young men and women are also generally more fit (or can be quickly gotten into shape), and have much faster recovery times from stress and exertion, better resistance to disease and can quickly learn new skills, which is why they are preferred as front line troops.

As well, young men's motivations are different, the desire for adventure, conquest and glory are powerful motivators, and political and military leaders have over 5000 years of experience in how to use these motivators for their own ends.

SOF operators, SF troops like Green Berets and to a certain extent Rangers and Paratroopers are generally a bit older and more mature/life experienced than their "Leg" or Marine counterparts (you to be a trained infantrymen before you volunteer to become a Ranger or Paratrooper, so maturity and life experience is often relative to other line troops), this combination of specialized skills training and life experience provides a huge edge over conventional and irregular forces.

In the context of ST, anyone can volunteer for Federal Service, and there is one instance where a recruit who is medically unfit for MI reappears later on as a cook since he refused to be released from service. Rico's father is a very mature man when he volunteers (and although he lost his wife and family estate, his corporation continues on; he has transferred executive authority to one of Rico's uncles).

Once again, Heinlein is making his point here; Achilles may have been fighting for loot, undying fame and personal glory but in this society you are expected to fight to protect and serve your fellow citizens and the taxpayers. The "baser" motivations like desire for adventure might still be there and get you in through the door, but unless you are willing to dig deep for the higher motivations, you will probably wash out of training (or request relief from non military Federal Service), eliminating yourself from consideration as a potential citizen.

A few points (part 1 of 2 tedious parts):

First, the argument that those unwilling to put their lives on the line for the state will be unwilling to do so in rebellion against it seems clearly false to me. Solidarity with one's government is not the same as solidarity with one's society. One can have none of the former, and plenty of the latter; one can wish to destroy the former, yet preserve the latter.

Throughout history the elites and the rest trade this role regularly back and forth. Radical anti-government sentiment mixed with strong social solidarity can be seen equally in the elites of Athens and the poor public of France or Russia. The difference depends on which class is most violently convinced that the state's burdens or restrictions fall unfairly on themselves. Almost all of Livy brings this point home, to the point of tedium. In general elites seem to have a far lower tolerance in this regard, judging by those examples and all others I can recall.

Now, military service to preserve or enrich one's society (or property) is often undergone even by those with anti-government sentiment, elite and poor alike, but make-or-break wars are notable for providing the pressures that spark revolutions. Again, there are many examples of this, and Athens/France/Russia all serve.

Given that noncom service is widely available for -anyone willing-, I doubt that much of the economic apparatus could be in private hands in Heinlein's world. The idea of fatted livestock herded by lean shepherds is evocative, but hardly realistic if we are to assume anyone may be a shepherd and the life of the livestock is free of pains and full of luxury while the life of the shepherd is the opposite. In this environment, one would expect even prominent "shepherds" to be easily corrupted and readily bribed, as was the case with the lower-class ephors in Sparta. If the herd does not outpace the herdsmen in luxury, then we return to the economic strength of the state being in the hands of the "citizens," the herd being Helots, and find a commonplace nasty oligarchy.

(part 2 of 2 tedious parts)

On another note, Heinlein's particular flaw (and it's a common one in authors that romanticize the military) seems to me his unabashed man-love for the resigned nobility of duty-bound professionals. There is one particular scene I remember wherein the sarge and the captain are discussing the necessity of disciplining some rogue cadet: it's this unsettling reciprocal tongue-bath between two grown men, with the unquestioned necessity of inhuman duty and the essential humanity of those bound to it as party favors.

Heinlein gets away with this in part because this ethos -does- exist in -some- who carry out disciplinarian doctrine, but so far as I can tell it is rarely evident in those who conceive of the doctrine. Heinlein is savvy in keeping the scope of his characters' agency very small and therefore sympathetic--the big brass are always ephemeral and mysterious, while we watch the little guys, whose only available means of ensuring society's survival is in abiding by the former's handed-down doctrines.

Also, disciplinary hierarchies based on shame or pain seem to make strange monsters of their enforcers in actual history. There is a subset of enforcers that carry it out resignedly and with humanity, true, but also another that does so with relish, at every opportunity, and in pure sadistic ecstasy. In romance usually one subset or the other is emphasized.

Incidentally I'm with Bertrand Russell that the Sparta love through the ages can be traced to nothing so much as the ideal versions espoused by Plutarch, Plato, etc., and not at all by the actual article. Aristotle has a more dismissive view, which matches some of the facts that are unexplained by the ideal--his contention that no Spartan can resist a bribe, for instance, is startling if one has read nothing but panegyrics for the ideal Sparta that never was, but the corruption rate of Spartan kings/generals abroad seems to support this contention. There is also their renowned slowness to action even against massive threat, and their disinclination for proactive warfare in general. Got to worry the Helots are going to revolt, I suppose.

Overall, I enjoyed the novel very much when I read it as a boy. I did not care for the moral philosophy bits, or the imagined society in general, though I was inspired by what the characters found in it.

@ElAntonius: that makes a lot of sense considering the morality of the books.

Heavy and pessimistic, yes. Realistic though? Maybe on one planet it's a realistic view--I haven't seen a Neanderthal lately. But in an entire galaxy? They're rather large, as I understand it. Just a thought.

@MRig:

Well, I don't think Heinlein was saying the humans had really any more right to the galaxy than the bugs...Starship Troopers did view humanity through the evolutionary perspective, and came to the conclusion that it is the nature of all species to go to war.

However, it's realistic if you consider that the bugs are genocidal, as well. Prisoner's Dilemma and all that. That theory dictates that you're better off slagging the enemy if you know he can slag you and you cannot communicate.

The ONLY reason we did not come to a nuclear exchange in the Cold War is because MAD only works when we can communicate. Without communication, if the Soviets were totally unknowable? We probably would have fired the nukes the SECOND we saw them get the bomb.

It sucks, but it's the nature of human as an animal. Elimination of threats and all that.

@ElAntonius: I'd say from a game theory perspective, it's tough to find a good fit. Iterated PD experiments yield "nice" but retaliatory strategies as the most successful, whereas the opportunity for retaliation after sustaining a "betrayal" (genocide) is nil in Heinlein's scheme.

Given the vastness of the play-field (the galaxy) the near-unlimited duration (longest possible survival), the likely mismatched strength of potential players (in technology, resources, etc.), and the effect of gained/lost resources on later iterations, there's no neat encapsulation of optimal strategy in iterated interstellar genocidal war.

If a long stalemate is likely, at what point does the cost of long fighting leave both parties vulnerable to another comparable party, whose effort is spent consolidating uncontested resources? It's a big galaxy, after all.

It would seem, since survival is the only goal, that knowing how to swerve, to avoid getting bogged down in war after war in one's tiny local area, is at least as important as knowing how to risk everything to gain a little by driving straight. Heinlein's vision of humanity doesn't seem particularly tooled for swerving. Say what you want of his humans, they don't seem the type to cut losses and pack everything up for a more peaceful neighborhood. In any true iterated interstellar genocidal war game, spending enormous resources to save a single planet, or small groups of persons, for example, would be ridiculous in purely practical terms.

I'd liken it to a poker tournament, with chips as resources. You can wield your big stack as a bludgeon and yet be a little more patient--picking off the desperate short stacks without much risk, and intimidating middling stacks because in conflict with you they are more at risk of elimination.

Likewise when you're really short, only high-risk moves are available and patience becomes impossible. Every move you make is all-or-nothing. Since your desperate moves can cripple the middling stacks, you can intimidate them; but any huge stack will be eager to pick you off at the first opportunity.

Now the above's an imperfect analogy for a lot of reasons, most of which have to do with less complete information and the fact that a player with enough resources may become impervious to all lesser players, but it fits better than PD, in my view.

@Anonymous:

What you're saying is certainly plausible in the more general sense.

But let's not forget that we're talking specifically about Starship Troopers...in that novel, there is certainly no option of just 'packing up'...clearly, both empires aren't after each others' resources, they're after each others' lives.

In that sense, retreat is probably not an option...the bugs will simply follow and exterminate you there. (Or at least, that seems to be the belief the humans hold).

I wonder, if the bugs full on retreated to a quieter corner, would the humans follow? Would they allow the opportunity for the aliens to rebuild and come back strengthened?

Would any strategist allow that?

Heinlein's scenario also doesn't seem to allow for iterative PD...it's winner takes all in the first round, and as far as PD is concerned both races have already taken the 'betrayal' option and are pursuing genocidal war...I suppose if the winner found mercy for the loser, we could discuss further iterations, or if the loser managed to retreat out of the winner's reach...but the book doesn't seem to think the former will happen or that the latter is possible.

I don't give a sweet damn about the arguments. I really like the book and re-read it about once a year.

@ElAntonius: Yeah, it's almost all speculation, particularly since we aren't given much of the big picture.

I think your question of what to do with a relatively weakened race is deliberately avoided by Heinlein--we are given the sense that the bugs are tough and smart like the apes, and that detente is impossible, but what happens to, say, the skinnies once the bugs are wiped out and the humans are still expanding rapidly? For Rico, violence solves problems and population pressure will eventually cause problems between neighbors, so I'm having trouble coming up with an idea of what mercy or coexistence between species in Heinlein's universe would look like.

On a total tangent, it's a bit strange that "neodogs" are biologically modified for combat effectiveness while humans are modified only mechanically. I suppose that's a dramatic necessity in some ways, but after all Heinlein is no stranger to human exceptionalism or rampant idealism in general. It always amused me that his utopia regularly suffers the same trope-laden reductive scorn he deals out to Plato's in the novel, another hopeless idealist. :-D

@ Anonymous

As far as neodogs go, I thought they were modified simply to make them easier to communicate with- they're scouts, not soldiers. Humans aren't modified because they don't need to be- physical strength for combat isn't as necessary, because the suit can take care of that. Same goes for eyes and other senses. Plus, suits are reusable- the reason robots aren't used is because at the time, computers were too large and unwieldy.

From a strategic perspective, the Federation is set up for a big time loss.

Each planet and star system must be conquered with a lot of Navy and MI blood, so a huge amount of resources must be spent to maintain the existing strength of the forces. At the same time, as the Federation expands either to colonize new planets or to chase down the Bugs, their force requirements increase exponentially. This would put a lot of stress on the economy, and the non-citizen taxpayers are likely to reach some sort of breaking point where they will not support the war effort anymore.

As well, since Federal service isn't universal, the pool of available manpower will not grow at anywhere near the rate required to prosecute the war, garrison important points or train the new intake. When 2000 recruits enter basic and @ 200 leave, the number of boots on the ground won't grow that fast, and when only 20% of the population is your recruiting pool, then things go south pretty quickly. (Even colonial planets with 80% of the population being citizens dosn't help, especially if the population is relatively small and these planets need the citizens to build the colony infrastructure).

Genocide might actually be the preferred military solution because the Federation recognizes these issues (now I am simply extrapolating from what we know of Heinlein's universe, none of this is RAH's doing!) and blasting planets with Nova bombs and burning Bug nests with nuclear armed MI is considered the most cost effective means of securing the Human settled section of the galaxy. Going further, by the time Rico reaches the rank of Lt Colonel and is in command of a battalion or brigade, the war might have settled into spasms of Navy warships firing kinetic energy weapons at relativistic speeds at any fully settled Bug planet, while MI troops raid planets which can be settled by humans but may have small Bug colonies not yet firmly established.

Since we have decades of new science and technology which Heinlein did not know in the 50's, this scenario is certainly the most Apocalyptic one; if the Federation needs living space that badly, settling asteroids and the moons of gas giant planets would seem to be a much better and more cost effective solution (and I don't see any indication that the Bugs are so inclined to settle in deep space).

Like most world building or polemic efforts, Starship Troopers was designed to illustrate a very limited set of points, and once you try to extrapolate too far or move beyond the bounds the author sets, then you are essentially debating how many angels can dance on the head of a pin. Now if JRR Tolkein had written ST......

My recollection of the book is hazy, as it's been many years, but:

Correct me if I'm wrong, but in the course of the novel doesn't the Federation suffer a big time loss, essentially reducing them to raids on weaker targets?

IE: your scenario already happened in context of the book (although towards the end IIRC the Feds recover enough to start thinking about big targets again)

I think the problem is that the bugs suffer the same problem. So short of total relativistic annihilation (which Heinlein attempts to sidestep by making the land desirable, but that creates the problems mentioned before), the outcome of any galactic war will always seem to fall to a stalemate.

But, I think the general sentiment is right. Heinlein wanted uber-Swiss with American sensibilities vs. the Alien Horde, and wrote the book to tailor to that. Worrying about things the Feds could have done better (or worse, depending on your point of view) is immaterial when Heinlein's real point was to make the ultimate elite military force, with the coolest equipment, to fight some totally faceless alien enemies.

>

> From a strategic perspective, the Federation is set up for a big time loss.

>

> Each planet and star system must be conquered with a lot of Navy and MI

> blood, so a huge amount of resources must be spent to maintain the existing

> strength of the forces. At the same time, as the Federation expands either

> to colonize new planets or to chase down the Bugs, their force requirements

> increase exponentially. This would put a lot of stress on the economy, and

> the non-citizen taxpayers are likely to reach some sort of breaking point

> where they will not support the war effort anymore.

I think that would depend upon the nature of the Federation. It's one thing if they're trying to pacify worlds that are already inhabited, by humans under a different government or aliens. But if these are empty worlds or are being xenocided to clear the way for fresh human colonists, the real question is "how long until these worlds are contributing?"

If we make a comparison to 4x gaming -- and barring real space exploration and conquest, it's as good a reference as we're going to get -- the contribution curve of a planet always starts out deeply in the red. Eventually it will go black and, after sufficient time, will contribute heavily to the empire's war effort.

The question of balance is important, of course. Early in a 4X game, the choice lies between military units, colonization units, infrastructure development, and research. Colony units cost oodles and you can't get anywhere without them. But once you setup a colony, you can't just let it sit there and pray the enemy doesn't come. Depending on the game, you're either building units to defend the planet or defensive structures. Civilization splits units into offense and defense units with the defensive types getting a bonus to make it harder for an opponent to sweep the board with an early rush. Master of Orion favored the notion of missile launchers planetside.

The bigger question you have to ask concerning Starship Troopers is what kind of range does the enemy have? In most 4X games, you can count on cities/planets in your interior being fairly safe. In Civ, you have to traverse the enemy's territory to get at interior cities. Your troops in the open are subject to attack by the enemy's forces. In space games like Master of Orion, your ships are given ranges due to arbitrary imaginary tech. You're forced to attack worlds on the enemy's periphery early on in order to get at his interior. Eventually you develop the range to perform deep raids on his most useful worlds and may not even try to conquer them for yourselves, rather you want to deprive him of their value.

So, is the Earth safe behind an interstellar string of fortresses or could a bug fleet go right from the frontier straight to Earth? If the later, then every planet has to be prepared for invasion and you're right, the cost would get pretty high.

>

> As well, since Federal service isn't universal, the pool of available

> manpower will not grow at anywhere near the rate required to prosecute the

> war, garrison important points or train the new intake. When 2000 recruits

That's harder to say. The United States didn't have the manpower to fight WWII and man the factories. Then someone said "Why can't we let the women man the factories instead?" and everyone realized their earlier thinking was very silly. We don't know the nature of the Federation economy and just how many people are necessary for normal operation. We also don't know what kind of production levels can be reached if they are operating in all-out total war mode.

> enter basic and @ 200 leave, the number of boots on the ground won't grow

> that fast, and when only 20% of the population is your recruiting pool, then

Or they may change their standards. The Japanese aviation schools had similar washout rates. They realized later in the war that they'd have been better off with a hundred good pilots rather than 10 great pilots. Earlier the concern was lack of airframes and they could afford to be picky. Later in the war they had plenty of airframes but not enough qualified pilots, not enough fuel to train them with, and not enough time to let rookies who had the potential to be great work through their inexperience.

> things go south pretty quickly. (Even colonial planets with 80% of the

> population being citizens dosn't help, especially if the population is

> relatively small and these planets need the citizens to build the colony

> infrastructure).

The backstory was vague enough that you could really push the story any way you wanted for a sequel, just as long as the ideas you propose are interesting and the story remains entertaining.

> Genocide might actually be the preferred military solution because the

> Federation recognizes these issues (now I am simply extrapolating from what

> we know of Heinlein's universe, none of this is RAH's doing!) and blasting

> planets with Nova bombs and burning Bug nests with nuclear armed MI is

> considered the most cost effective means of securing the Human settled

There's really not any need to fight on the planet's surface if your only interest is denying it to the enemy. If you are inhumane, or if your enemies don't deserve human consideration, nuking from orbit (or dropping giant rocks) is always an option. If you are looking to be humane, a planetary blockade is a safe bet. The real question is how production works in that universe. In most scifi universes, getting off the planet is hard and you really only want to move people up and down the gravity well. Most manufacturing -- especially for starships -- is done in space. So putting particle cannons and retrograde homing mines would probably do the trick. If it's a crazier Star Wars universe where whole fleets of starships can be built on the planet and sent into space, there may be the concern of the enemy staging a breakout of the fleet. This is assuming they have something like planetary siege bases buried a hundred miles underground, the kind of bases that would take an extinction-level event to destroy from orbit. If you want to destroy that base without destroying the planet then you have to take and hold the ground above it and then drill down through whatever extra armor is above it to destroy it.

In any realistic setting, planets would seem to be giant targets that cannot be adequately defended. Unless the technology supports the idea of planetary shields or some defense mechanism that can instantly and reliably obliterate any potential attacker, that itself could not be saturated and destroyed... I think the rule of thumb is pretty much any defense can be countered given sufficient time for preparation by the attacker. The only really sound defense is remaining hidden. This is the Puppeteer defense.

> section of the galaxy. Going further, by the time Rico reaches the rank of

> Lt Colonel and is in command of a battalion or brigade, the war might have

> settled into spasms of Navy warships firing kinetic energy weapons at

> relativistic speeds at any fully settled Bug planet, while MI troops raid

> planets which can be settled by humans but may have small Bug colonies not

> yet firmly established.

I think the more likely scenario for massive MI deployment would be on human-held worlds trying to fend off the bug invasion. That presents the scenario of an established infrastructure that we're trying to defend in the hopes of not having to write everything off. And this is assuming the bugs don't decide to do what they can to nuke things from orbit.

I've not quite yet seen this in a scifi setting but someone on the list mentioned the limited thinking with wormholes. If you have the wormhole in space, why not put it on the planet surface, especially if you're engineering one? Take the tram from downtown to the local wormhole and pop out on another world. So if you can do that, why can't the alien invasion come through the wormhole as well? So it's never really fought in space, it's fought planet to planet.

Oh wait, you know what, I take that back. That's what they did in Total Annihilation. I don't think the name of the thing was wormhole but there was no space transport, the war was fought planet to planet. Presumably distance from one to another played some role since there was an orderly progression across the galactic map.

>

> Since we have decades of new science and technology which Heinlein did not

> know in the 50's, this scenario is certainly the most Apocalyptic one; if

> the Federation needs living space that badly, settling asteroids and the

> moons of gas giant planets would seem to be a much better and more cost

> effective solution (and I don't see any indication that the Bugs are so

> inclined to settle in deep space).

Yeah. You really have to tailor your setting carefully to create the kind of fighting you want, so there's a reason why it's the way you want it rather than a big gaping plot hole. For example, in Dune the fighting man was considered the best weapon around and I think they said something in the backstory about being able to win a planet with two hundred fighters. The whole point was that transport remained very expensive and it was more economical to settle matters of combat with trained men and put your effort in the training than in trying to ship millions of mens and gigatons of fighting equipment. Of course, that's exactly the kind of system ready to be swept away. The Fremen Jihad did just that. The limitation of the Guild not providing transport for this sort of thing was removed when Paul incentivized them with his spice stick. Also analogous to the courtly, gentlemanly, predictable European warfare fought as elaborate chess matches got blown out of the water by Napoleon and his concept of total war.

>

> Like most world building or polemic efforts, Starship Troopers was designed

> to illustrate a very limited set of points, and once you try to extrapolate

> too far or move beyond the bounds the author sets, then you are essentially

> debating how many angels can dance on the head of a pin. Now if JRR Tolkein

> had written ST......

>

Too true.

>

Welcome to a couple of new commenters, and thanks, Bernita, for the reality check.

As I recall, neodogs had greatly amped up intelligence (in the general, not military sense). Heinlein probably ignores the implications of modding for the reason Thucydides gives - it had nothing to do with either the story or any messages Heinlein wanted to toot in this book. Neodogs were just a bit of local color.

The same, writ big, goes for trying to make sense of alien relations, the overall interstellar situation, and the grand strategy of the war. He sets the whole thing up to be a war against giant bugs for chrissakes. (Well, 'pseudo arachnids.')

In fact - and I have never seen this in the much too extensive literature on Starship Troopers - this book, much more than most Heinlein, seems rather cinematic, as if he intended it to be made into a movie. Obviously not Verhoeven's.

You've got your cool guys in mecha suits, your spiffy deployment tech, your aforesaid giant bugs, and a looong opening sequence, er, passage of total badass combat.

Since I don't much like Heinlein's political theorizing in the book, it was no skin off my face if Verhoeven wanted to trash it (though I would have just left it on the cutting room floor). But why leave out so much visual candy just begging to be shown?

@Rick: I think Verhoeven's budget simply couldn't sustain a representation of the MI that was plausible or impressive.

To return to things straight from the book, there's much talk about the moral difference of those willing to serve in the military as compared to civilians, and that the effect of attracting "aggressive" elements to serve the state inoculates the state against revolution.

I think these are pretty idealistic and untenable, and the no-nonsense, tough-guy, pragmatist presentation is pretty silly (unless you're a young adult!).

As I said above in boring posts no one read :-D, one's government and one's society are not equivalent--one may refuse to die for one, yet willingly die for the other. Voluntary military service is no panacea for aggressive elements that dislike the government or certain aspects of society (the enlistee and bronze-star-awarded Timothy McVeigh comes to mind). External threats that are seen to threaten society (in reality or otherwise) may yield near-universal support for military service out of fear, but also may radicalize opposition to government out of the same fear.

Then there's the whole rigamarole about deriding moral philosophy for not fitting "facts," or assignments to draw up "proofs" of moral arguments. Do they not teach Hume down at the War Colleges, or have philosophical as well as technological advances been made? Anyway I'd like to see Rico's proofs for some of the moral assertions in the book, even if my symbolic logic is a bit rusty.

All that said, I like Heinlein quite a bit and don't want to be too down on him, despite his politics and idealistic posturing, which I -dislike- quite a bit. Asimov and Philip K Dick, from what I've read, felt much the same way.

Jollyreaper, the Bugs were able to strike Earth early on in the Bug war, and the MI makes one abortive invasion against the Bug homeworld in the book and ends with the start of another drop there, so getting around does not seem to be a problem. This means that every planet is a potential target, and resources must be spent to protect every one of them or leave them to their fate.

The analogy of Rosie the Riveter filling in the files for the depleted ranks of Federation Citizens simply is impossible in the construct of Starship Troopers; the taxpayers are not Citizens precisely because they would not volunteer, and instituting a draft would fundamentally alter the nature of the Federation and its society.

Going deep into history, the Classical Greek city state of Athens was radicalized when the free born rowers of the Navy were able to gain political rights, arguing they had equal ability to middle class Hoplites in protecting the realm. The massive growth of the assembly eventually destabilized Athens because the assembly could be swayed by demagogues to vote for outrageous things (the Mytilenian Debate is the best example, the assembly was induced to vote to kill all the men and enslave the remainder of the population of Mytilene before rescinding the order the next day). This is the sort of thing the ancient Greeks disaproved of (most of the polis had strict eligibility limits for citizenship; a timocracy), and the Founding Fathers of the United States had similar reservations about democracy, crafting a series of checks and balances to prevent power grabs and mobs riding roughshod over the rights and will of the people (checks which have sadly eroded over the 20th and early 21rst century).

Sparta had the opposite problem, the "Similars" were the only fully enfranchised citizen class, but as it was easier to kick out people who transgressed against the rules and mores of the citizen class than to raise up new citizens, the ranks of the "Similars" constantly declined.

Since the Federation is a form of Timocracy, then either the rules of eligibility have to change to ensure manning of the military and the direction of the State (with the constant threat of radicalization), or the Citizens will be bled white and cease to be an effective ruling or fighting class. Once again, this is in the realm of pure speculation, Heinlein simply does not provide enough background to make any clear predictions either way.

@Rick:

AFAIK, Verhoeven had already completed the script as Bug Hunt! or some such before he even became aware of Starship Troopers, which he never read.

The studio decided to attach Starship Troopers to it due to tangential similarity and marketing reasons.

The troops lacking power armor is part of his original vision: send woefully underequipped soldiers, barely trained, to die gruesomely for some nebulous cause.

You know, I just realized this when you were discussing Rosie the Riveter: what will the Federation look like after the war? Will all these civilians contributing to the war effort use it to start a "people's rights" movement?

I have been reading this site with great interest for some time now, but finally decided to offer some of my own comments, since this thread concerns civilizations (which I do understand to some degree) and not complicated mathematics (which I do not understand at all).